“Some twelve years ago a hundred or more citizens agreed to give ten dollars a year each for the purpose of starting a Toledo Museum of Art. They did not make the mistake of calling themselves club, society or association, but took the name of the thing itself which they wished to create; and so this thing that had no existence other than a name had to be conjured forth into some tangible and visible form. An art association might have existed indefinitely performing its functions admirably without even getting beyond the proportions of an association. However, they had the temerity to christen their hopes by the ambitious title ‘The Toledo Museum of Art’ and it thereupon became incumbent upon them to produce at once a result to justify the name.” Mrs. George Stevens, from a paper read at the Fourth Annual Convention of the American Federation of Arts, held in Washington, D.C. 1913.

A Man and a Dream by Nina Spalding Stevens

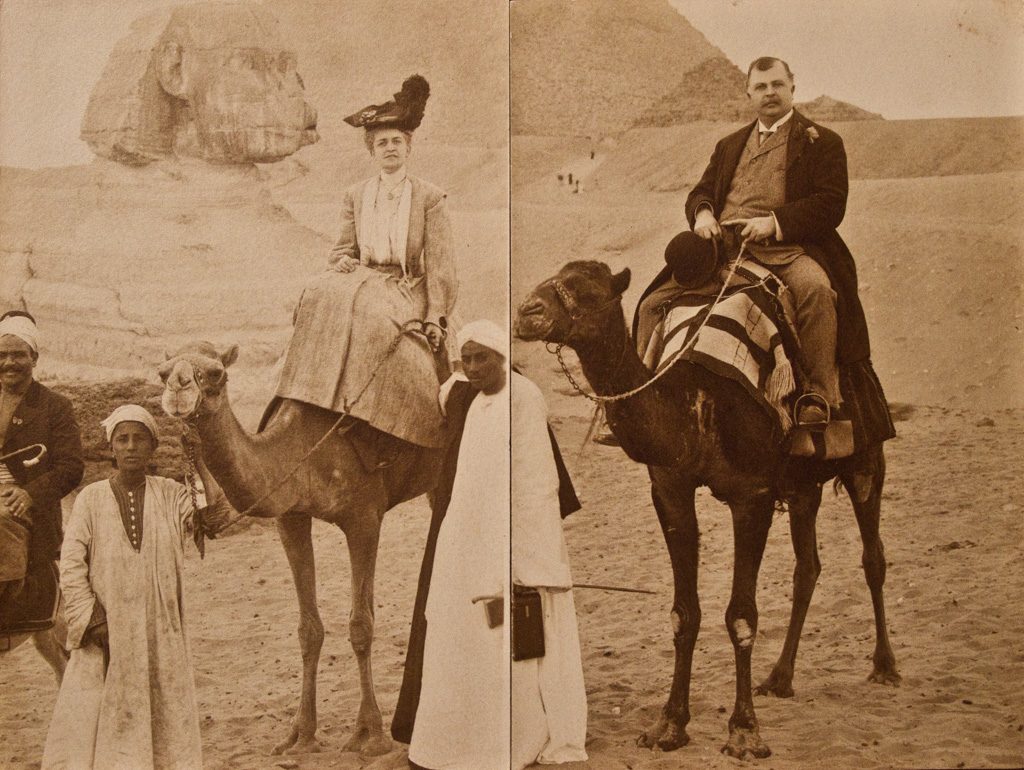

George Stevens was the first real director of the museum. His wife, Nina, served as the assistant director. Edward Drummond Libbey was the president of the museum and the main benefactor. They were great friends. In regard to the creation of the museum, they had an interesting synergy as to the way Libbey would teasingly challenge them to the task of raising say $50,000, that he would then double. This went on for 25 years until they died — Libbey in 1925, and George Stevens in 1926. Nina Stevens wrote this memoir in 1939. Before creating the Toledo Museum, George had experience as a circus performer, poet, advertising man, theater manager, opera singer, tourist guide, actor and newspaper columnist. Nina was a writer and artist born in Port Huron, Michigan. Bold, progressive, daring, courageous and outrageous, they epitomized the collective personality and creative force of Toledo.

How George and Nina met, 1902 p. 24

I met George Stevens first in Toledo, where he lived, and I was visiting. He always insisted that I married him, and perhaps after all he was right. I think that I must have fallen immediately in love with him. We talked eagerly through a dinner, and after dinner, when I suddenly felt a distinctly antagonistic atmosphere all about us. I was monopolizing one who belonged to them all. After he had been duly recaptured by them, he sat at the piano and played and sang while they crowded around, joining in the choruses. He sang a tender little love song, looking at me, as I was the guest, and it made my heart turn over. It was a nice sensation, and I liked it. He walked home with me, notwithstanding that I had come with another man, quite as though it were his right, and I liked that too. The next day he arranged his engagements to spend the evening with me. Again we talked, really talked, about our ideals, our ambitions, our writing, for that was what we were both anxious to do. We never attained our goal. It was that desire which brought us together and made us interested in each other but within a year we were to turn whole-heartedly to another work, both of us, and pursue it together for twenty-four years.

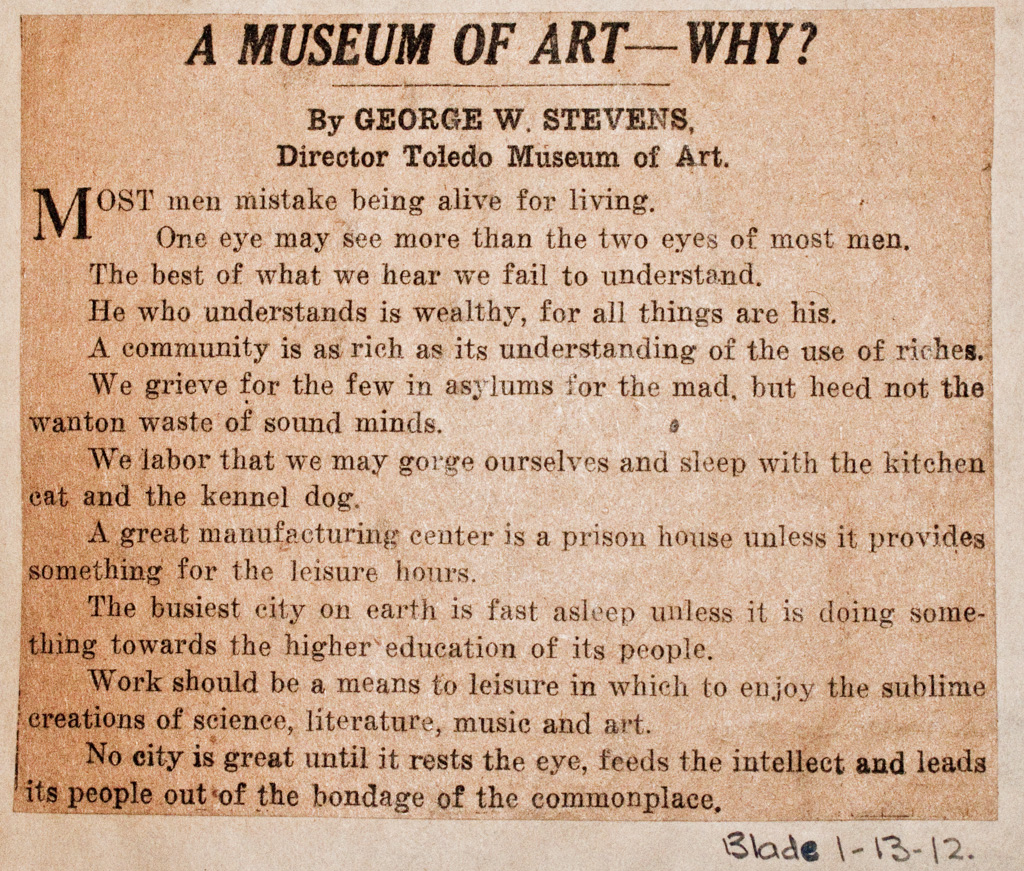

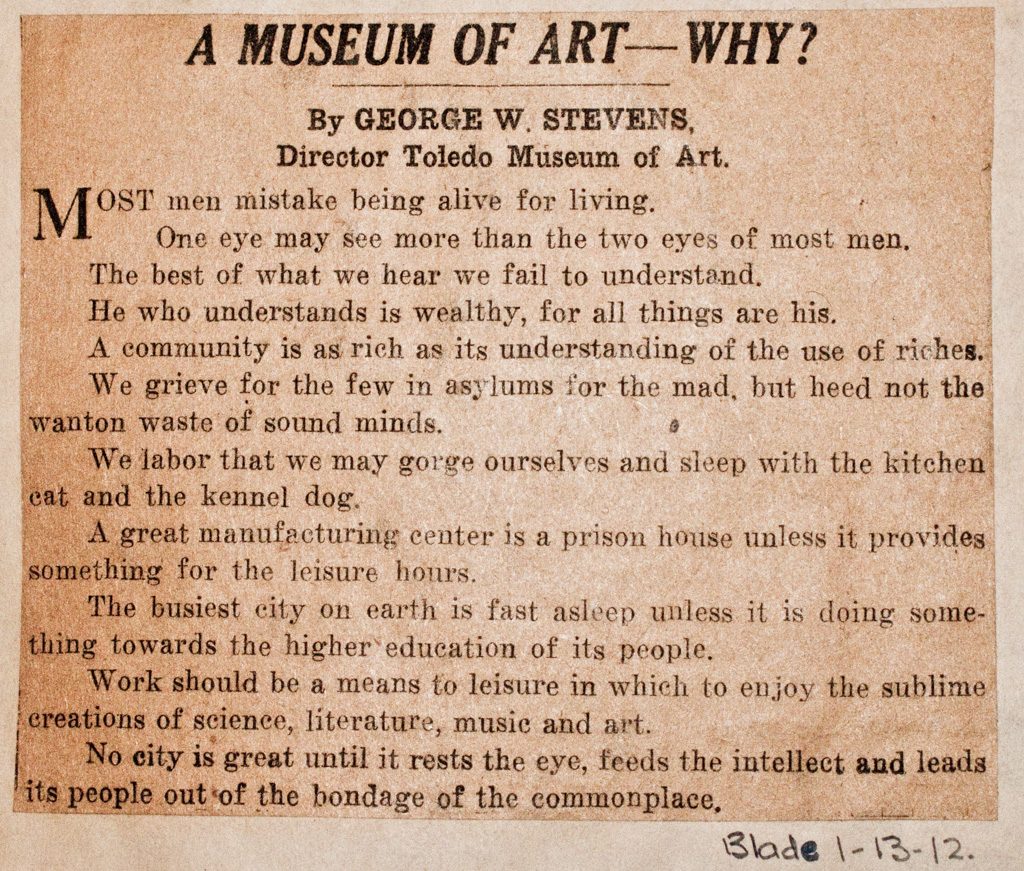

George Stevens Manifesto published in the Blade, January 13, 1912.

George Stevens becomes director, 1903 p. 30

The Museum was founded in 1901. The idea of a Museum of Art for Toledo emanated from the Tile Club, a group of artists of whom George was one. He was also one of the one hundred and twenty-six charter members of the Museum and on the Nominating Committee of its Trustees. His direction of the Museum began in 1903, and came about with characteristic unexpectedness.

One afternoon in October of that year, the fifteenth, I see from the records, Charlie Ashley dropped in to our apartment in the Monticello. “I’ve just come from a meeting of the Trustees of the Museum,” he said, “and we have decided to give up the project. Whiting [who was the secretary] has resigned and there seems to be nothing else to do.” After some discussion, in which, as I remember, George expressed deep regret, Charlie said, “If we had a man like you as director perhaps we might make a success of it”.…..”Well, why not?”said George, with not even a glance in my direction. Within twenty-four hours his nomination was proposed to the president, Mr. Libbey, and signed, sealed and settled forever. And that is how George Stevens became the Director of the Toledo Museum of Art.

Libbey’s fundraising proposal to deed the building, 1908 p. 104

In a year of such depression that the Trustees sat and looked at the floor when raising money was mentioned, Mr. Libbey had promised to deed the Madison Avenue property then occupied by the Museum, to the association if George could raise fifty thousand dollars by May, and something had to be done about it. George and Carl Spitzer organized the campaign. The meeting was set for Saturday afternoon, and the Trustees filed out from it as though they had just attended a funeral. There was the possibility that they had, but George would not admit it.

Mr. Newton’s deathbed bequest, 1908 p. 105

We were breakfasting with Mr. Gosline the next morning. Mr. A. L. Spitzer, Carl’s father, was there. George, full of enthusiasm and confidence, outlined his plans, and Mr. Spitzer said, “I will start the campaign by pledging one thousand dollars.” We all danced around in excitement. We had lunch with Carl and Edna Spitzer, and during the luncheon we made a list of all the people we could think of who might give a sou.” There’s old Newton,” said Carl, “who should be interested, but he’s dying.” George and I looked at each other and said “Mr. Hattersley” in unison. “Go and call him up and ask when you can see him.” I flew from the table. “Right away,” was the answer I came back with. I left the luncheon and ran the little car down to his house. He heard me through, about the children, the influence on the town, etc., etc., and said he would talk with Mr. Newton, but as he was waiting to die, and his affairs were all in order, Mr. Hattersley doubted very much if anything could be done about it. That night he called me up to say, “I gave Newton the talk just as you gave it to me. He wants you to come to see him tomorrow afternoon at two o’clock.”

I had never seen death, nor its approach, and always had feared and avoided it, but now something stronger than fear was dominant in me. George was not even sympathetic. “What shall I say?” I asked. “Never worry about what you have to say. The other person will always do the saying and give you your cue.”

I found a solitary old man with a long white beard in a red flannel nightshirt, sitting in a straight-backed yellow oak chair, his feet on the rounds of another chair on which were a pitcher of water, a glass, and a bottle of whiskey, his hands folded over the crook of a cane, his chin on his hands. There he sat awaiting death. The nurse, on our way up the staircase, whispered to me that he had only two more days at most. I sat down, and his large hollow eyes searched my face as he slowly asked me questions which I quietly and with awe answered. Then he handed me a note for five thousand dollars all made out and ready for me, which he said must be discounted at the bank. Before I could express my gratitude to him he said, “Go downstairs and take all the books on art that you can find, besides the pile which the nurse has made. And send this afternoon for my paintings. Goodbye, and thank you for coming.” That was all. He died the next afternoon.

Building fund created, 1908 p. 109

Museums were being built and wanted directors. Several most tempting offers were received by him, but the Toledo Museum had become his child and he would see it through. He believed in its future and would not abandon it. These offers gave him courage, however, at the end of 1907, to make an appeal to Mr. Libbey, the President, and to the Trustees, for a Museum building. He argued that as long as, we occupied a temporary rented building no one felt like making gifts of any great importance, but once in a permanent Museum on our own ground, the rest would come.

Then it was that Mr. Libbey offered to deed to the association the property which the Museum was occupying if George and the Trustees would raise fifty thousand dollars by the first of May, 1908. This was the start, and, as I have already said, in the face of one of the most serious depressions of a quarter of a century, the money was raised, and more, which so pleased Mr. Libbey that instead of giving the old property to the Museum, he doubled this sum and added to his gift the present site of the Toledo Museum of Art. This had been the estate of Mrs. Libbey’s father, Mr. Maurice A. Scott.

The twenty thousand children who had attended the talks at the Museum voluntarily gave pennies to the Museum fund which, when George had made a great mound of them in a downtown bank window, with rather a touching poster, gave us considerable publicity, not only in Toledo, but in the nation, and helped the campaign appreciably.

Stevens’ dues collecting techniques p. 112

The Reinhardt Exhibit and the Roullier Collection, which had become annual events, the Toledo painters, the men and women artists being now combined, the Camera Club Exhibition and some ten other collections which could be paid for with our small funds, required time and management. Yet it had all been accomplished with one secretary, one young woman at the entrance desk who also did the typing, one janitor and an occasional evening’s help of the Woodruffs, who ran an art shop. In the year the secretary had added one hundred new members and George wrote in his Museum News most characteristically:

Since September last we have added just one hundred new members to our list, all good names – men and women who are really interested. We now have over five hundred supporting members eager to pay their dues without making us spend twenty dollars worth of time to find out when we can call again for that ten dollars. On the rolls of every organization, as on the books of every business concern, there is always a goodly percentage of dead-beats, hangers-on, good-for-nothings and professional irresponsibles. With these we no longer have an acquaintance. They have been swiftly and quietly dropped from our rolls. Perhaps they are wondering why our face is seen no more in their land. Well, let them wonder. We are conducting a Museum and not a collection agency. We have’ demonstrated the fact that there are enough loyal, responsible public-spirited citizens in Toledo to support a first-class Museum of Art.

He of course took pains to send this number to all the members whom he had characterized so unflatteringly, with the amusing result that several were insulted into sending their checks. One man wrote him a letter saying, I’m neither a dead-beat, a hanger-on, a good-for-nothing nor a professional irresponsible, but I always delay sending my check until I have received three of your personal follow-up letters, with which I amuse my family and my friends for days. You will receive my check promptly after this.

For some time George and I had gone ourselves, in spare moments, to offices and homes to try to collect back dues. It was a most illuminating psychological study. There were people within the circle of our own acquaintances who felt it their God-given right to take all the advantages of the Museum without paying for them. To handle these cases and not incur their enmity took some tact. They would put us off smilingly, or tell us to come again, or to go and see their wives or husbands. George’s outburst in the Museum News was the result of many of these encounters. Sometimes we said very well, we would report their answers to the Trustees it the meeting which was to take place next day. That usually produced a checkbook. It was a great relief to have Miss Brown, the secretary, take charge of this collecting.

Another campaign for funds (1911) p. 154

Before the new Museum was opened, there had to be still another campaign for funds. The outside of the building was complete, but an additional one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars was needed for the interior. Mr. Libbey offered twenty-five thousand dollars if George and the Trustees would raise the one hundred thousand. And they did. George’s psychology proved correct. There stood the Museum now on its own ground, concrete evidence of perpetuity. It was no future project, this, but the Toledo Museum of Art in marble and mortar, ready to take its place in the life of the city. While the money did not exactly pour itself into our laps, still it came, this larger sum, much more easily than that first fifty thousand.

President Taft visits the museum, 1912 p. 168

The American Sculpture Society filled the entrance court with interesting works, among them a bust of Wm. H. Taft, who was then President.

While this bust was still on exhibition, the President came to Toledo to make a speech, and at the same time paid a visit to the Museum. George in his wheel chair and black Joe pushing him, Mayor Whitlock, Mr. Secor, the Vice President, Mrs. Secor, and Mrs. Sidney Spitzer, were there to receive him. The entrance to the Museum was lighted up, and Campbell and the guards on the steps awaited the moment of his arrival. The appointed moment came and passed, the guards in their best new uniforms were covered with snow, Campbell swept and re-swept a path to the street, and still we waited. Suddenly a face appeared at one of the windows and announced that the President was down at a back entrance, which was locked and barred. All our efforts had been concentrated on the front. The keys of the back door were in Campbell’s pocket. I, in evening dress, tore down through the snow to find him in the street and together the two of us rushed back into the Museum and down endless stairs and halls and shakily unlocked the bars and doors outside of which the President was waiting. The President smiled blandly but his aide snapped at me, “Do you realize that you have kept the President of the United States waiting fifteen minutes in this storm?” I snapped back, “We did not expect you to bring the President of the United States to the shipping room door.” Whereupon the highest dignitary in the land took my arm and twinkled at me some pleasantry about it being the appropriate place to deposit heavy loads, and we all laughed.

George Stevens meets Blake-More Godwin (1914?) p. 183

One day came a letter from Princeton, from a postgraduate student, setting forth clearly and simply his qualifications for Museum work, a letter so compelling that George sent for the writer to come and discuss the matter. That was Blake-More Godwin.

He arrived unexpectedly just as we were all driving up the river to picnic on the rocks, the Goslines, Carl and Sidney Spitzers, the Bells, the Secors and the Goodbodys, so we took him along. What an introduction he got to his life’s work at the Museum! After supper, which was most successfully delectable in the sunset, when George with his best bass rod was out on a point of rock casting for small-mouthed black bass, and the rest of us were lying about under the high bank that towered above us, none of us giving a thought to the clouds beyond the bank, suddenly, with a crack of thunder, a primeval deluge and night fell upon us. Unable to see a thing, we tried madly to put the picnic dishes back in the various baskets. Some of the fittings, I’m sure, have not found their right places yet. George took down his rod and thrust it at me to carry. Always our first concern was to keep him dry and warm and free from impediments. In the scramble up the bank, we chose what in the dark looked like a path. It developed into a torrent rushing over a clay bottom. When we got back to our house to dry out and finish the evening before a log fire, clay was clinging to our legs up to our knees under our skirts, and before the flames the men’s trousers grew as stiff as pottery. We scraped off what we could from them, gasping with laughter, and became almost hysterical when Blake explained in a gentle drawl that they were “the only pants he had” expecting to have arrived for a business talk and to leave immediately. I think we all took him to our hearts at that moment.

Early the next morning I drove out again from town and recovered all I could of what we had lost, including George’s rod, of whose absence I spoke not a word until it was safely returned. Blake stayed in bed until his clothes were cleaned while George sat beside him and they held the important “conference” for which the young man had come. It was a conference that was to bring to George not only a future efficient Director of the Museum but a dear son in their relationship and a lovely and devoted daughter. When I came back from the picnic ground I was presented to “the new Curator of the Museum.

King Albert’s visit to the museum, 1915 p. 191

George, for the occasion, had put on a suit that had just come home from the presser. In some unaccountable way, due no doubt to the malice so well known in inanimate objects, this suit had come back with a long ravelling hanging down from the back of his coat, like a tail. I noticed it just before the royal party arrived and tried to call his attention to it, but George was so busy talking with Mr. and Mrs. Libbey, or telling people where to stand so as to make the best effect that he paid no attention to me and I could not lure him into the office to remove that ludicrous tail just where a tail ought to be. So picking up the only available scissors near me, some long paper shears, I tried to stalk him from behind and cut it off right there. There was no time to be lost and I took a chance of not being seen. Alas, Mrs. Hineline, the clever writer on the morning Times, of all people did see me, and that homely incident appeared in her account next day of the glory and panoply of the royal visit. She saw an amusing contrast which made us home people very homely indeed.

1916 endowment fund campaign and the high cost of stupidity p. 194

The campaign for an endowment fund of six hundred thousand dollars was closed December twenty-sixth, 1916. The full amount was obtained within less than six weeks. Of this Mr. Libbey gave four hundred thousand dollars. In 1917 George announced to the Trustees that the Museum must be doubled in size. “Do you know,” he wrote, “that the high cost of living is not our greatest menace? Will you believe me when I say it is the high cost of stupidity? We know all about how to create spineless cactus, seedless oranges and edible grapefruit, but we are apt to overlook the fact that we could improve the human brain to the same degree and with the same expediency if we so desired. Our education is, or has been, lopsided. Art is a most necessary expedient in our lives which we have overlooked entirely. Art should enter into every human activity, into the making of our homes, and the building of our cities – into every product of the manufacturer, and into every detail of merchandising. Fifty per cent of everything we fashion without the aid of art is money wasted. The laws governing art are well defined and are readily understood by a child. After the brain becomes ossified in the adult, however, it is hard to introduce any new ideas. The plastic mind of the child immediately grasps the principles of color harmony, of composition, of balance, of rhythm and those other and similar elements which create beauty, utility and perfection. By our present rule-of-thumb methods when we have learned to live we are about ready to die. Every month five thousand children visit the Toledo Museum of Art. They come of their own volition. Art is the panacea for most of our ills and must prevail if we are to be a great nation.”

Campaigning Libbey in Paris, 1922 p. 200

George was not feeling very well that summer, and our finances were rather low, what with the trip I was taking, and the death of his mother, but he felt that such a wonderful opportunity to talk to Mr. Libbey about the needs of the Museum must not be neglected. We were their guests, from Paris back to Paris, by way of Burgos, Madrid and Seville, by automobile, then George and I returned to our work in Toledo.

Through it all, George, of course, had lost no time or chance in pressing the subject of the Museum upon Mr. Libbey. Mr. Libbey mischievously countered these maneuvers by asking George to raise another two million dollars on his return to Toledo. Poor George! By this time he had asked so much money from the people of Toledo that he could scarcely look Washington, or Lincoln, or whoever it was at that time on a dollar bill, in the face. He took the thing very much to heart, and was not at all his gay and humorous self. It was a battle of wits between the two men.

Secor donates paintings, 1922 p. 201

That same year Mr. Arthur J. Secor, the Vice President of the Museum, came to George’s office one Sunday afternoon and said, “I watch the procession of people, men, women, children, passing by my house on Sunday, a never ending file up the street to the Museum, and I turn around and look at my collection of paintings and feet selfish. I am giving them all to the Museum tomorrow.” It was a gift that aggregated half a million dollars. I think George almost fainted at this great sudden and unexpected gesture. The whole city rejoiced. Mr. Libbey gave a reception for Mr. and Mrs. Secor at the Museum when the paintings were installed. They were mostly of the Barbizon school, and very fine examples. One of them, a Rousseau, was invited to the great retrospective exhibition of French art at the Paris Exposition of 1937.

Libbey doubles the size of the museum at the cost of $850,000, 1923 p. 204

The great announcement was made in 1923 that Mr. Libbey would himself “double the present unit of the Museum, at an estimated cost of eight hundred and fifty thousand dollars.” This seemed to be the answer to all of George’s life.

Libbey dies and leaves the museum a fortune, 1925 p. 208

Mr. Libbey was the first of the two men to die. He caught a cold and then pneumonia, and his great, kindly and helpful life was over. just as suddenly as that. The whole city went into mourning. Even the public schools were closed. A great part of Mr. Libbey’s fortune was left to the Museum. George’s fears for the future of the institution were stilled. Plans which are not workable after the departure of the originator are not destined for eternity. When the torch is flung far with the certitude of capture by those whose outstretched hands are ready to grasp and carry on for a space, that is success. To march on in a new time, under altered conditions, with fresh conceptions of those ideals, is intelligent loyalty. That George did not live to know the complete fulfillment of his plan has seemed very bitter to me, but sometimes for a moment I see clearly, as one finds suddenly a patch of blue in the shifting clouds, and I know.