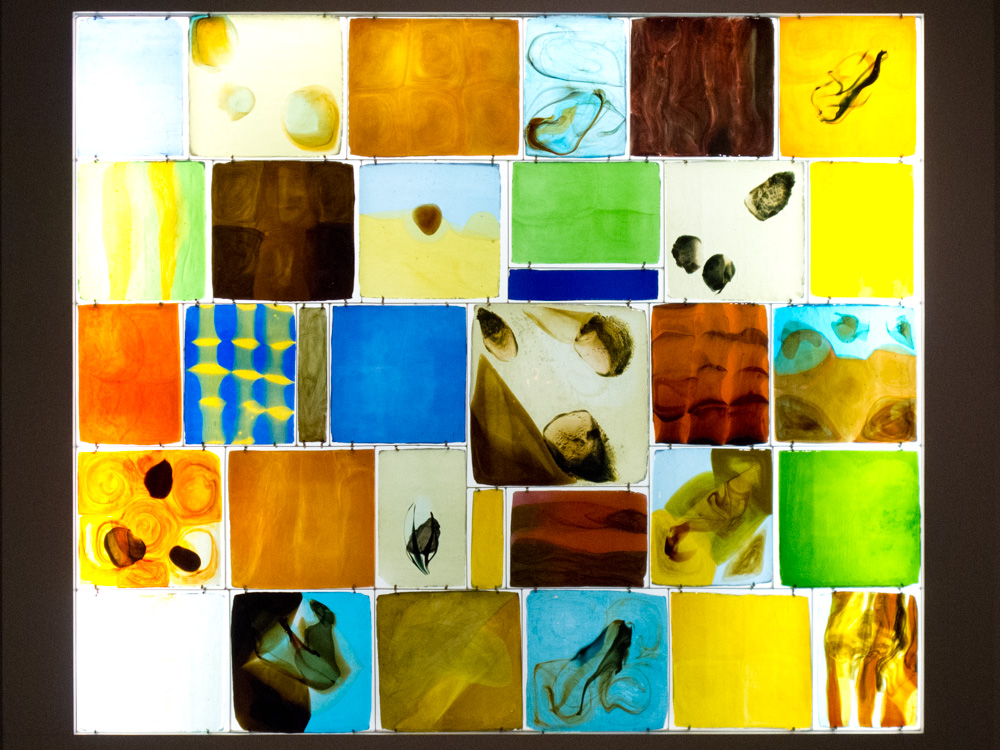

As the glass gallery neared completion, the designers suggested for the entrance a map of the world on which could be indicated glass centers throughout history. It seemed to me that there should be a more dynamic way to express glass. I asked Nick [Dominick] Labino. a glass engineer and also a glass craftsman, if we could make an abstract mural of glass which would fit into this rectangular entrance. He said he had never done anything like that in his life, but by this time he had become so fascinated with glass blowing that he made his own glass furnace. He said he would like to try it. so he went to work and blew some shapes. He’d make a bottle, and while still molten, squash it so it became a flat piece, because we wanted to light this glass mural from the back. These squashed glass bubbles were beautiful, but round in shape, and we needed rectangular shapes to place in the rectangular entrance. Nick didn’t know how to make rectangular shapes, but he was inventive, and one day he said, “I think I’ve got it.” He had built a new kiln to cool the glass. Nick had built a big, rectangular floor piece,into which was poured the molten glass. He poured different colors one on top of the other, and began to get the effect he wanted. He showed me the first small rectangular panel and said, “Now, I want you to know, nobody else could do this, because the great trick is when you put two colors of glass together they tend to crack, and if I didn’t know as much as I did about the chemistry of glass, I wouldn’t be able to do this.” I said, “That’s fine, Nick, a good start, but we’ve got to have many, many more, because what we’re trying to do is to create a pattern to make a mural about ten feet high, which will be lit from the back. I know you can’t make a ten-foot piece of glass, but we can put these panels together to form an abstract pattern.”

Every weekend my wife and I would go out to see Nick and his wife—they together were developing the designs and colors. Each week there were a few more pieces and they became very inventive in design and color. I’m sure Labino’s wife was very helpful in that. She had been an art teacher and she knew color.

Finally Nick built a wooden frame approximately the same dimensions as the mural,with shelves every twelve inches or so. Each week we took the pieces of glass and simply set them on these shelves, with a light behind them, and in that way we could begin to make an overall design of the varied glass rectangles.

We had to design it as one would a painting. It was a kind of communal abstract design of colored glass rectangles.

Finally, when the overall design seemed satisfactory, Nick and his son-in-law built a permanent steel frame to hold the glass, and together they installed the mural in the entrance to the new glass gallery. The architects provided a lightwell in back to light the glass. It is a vivid, dramatic installation. It says, “This is glass,” if anything ever could, and it was done by a contemporary craftsman right in Toledo, Ohio. After it was finished I asked,

“Nick, what are you going to charge us for all this time you’ve given us and all this beautiful glass?” He said, “My friend Boeschenstein gave the gallery, the least I could do is to give the mural.” Later on, this mural led Labino to design other murals throughout Ohio. He used similar glass panels for a mural at the museum in Columbus, Ohio, and later for a mural in the State House there. So, that’s the story of glass. The glass came from Mr. Libbey, and the collection was developed and expanded by the museum. The gallery was built by Mr. and Mrs. Boeschenstein, who gave the money for it, and the glass mural was given by one of the great glass craftsmen of our time.

— Otto Wittmann, The Museum in Creation of Community, Oral Interview by Richard Smith for the Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities