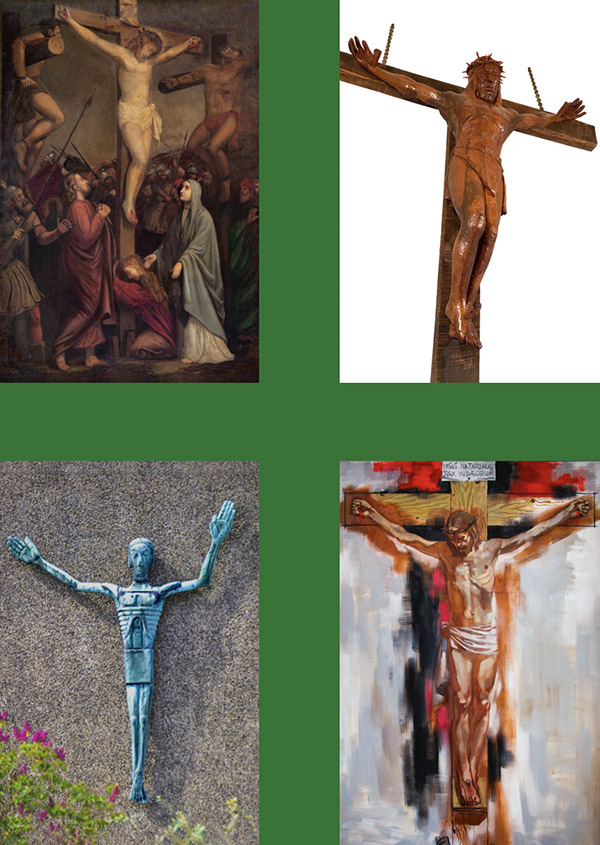

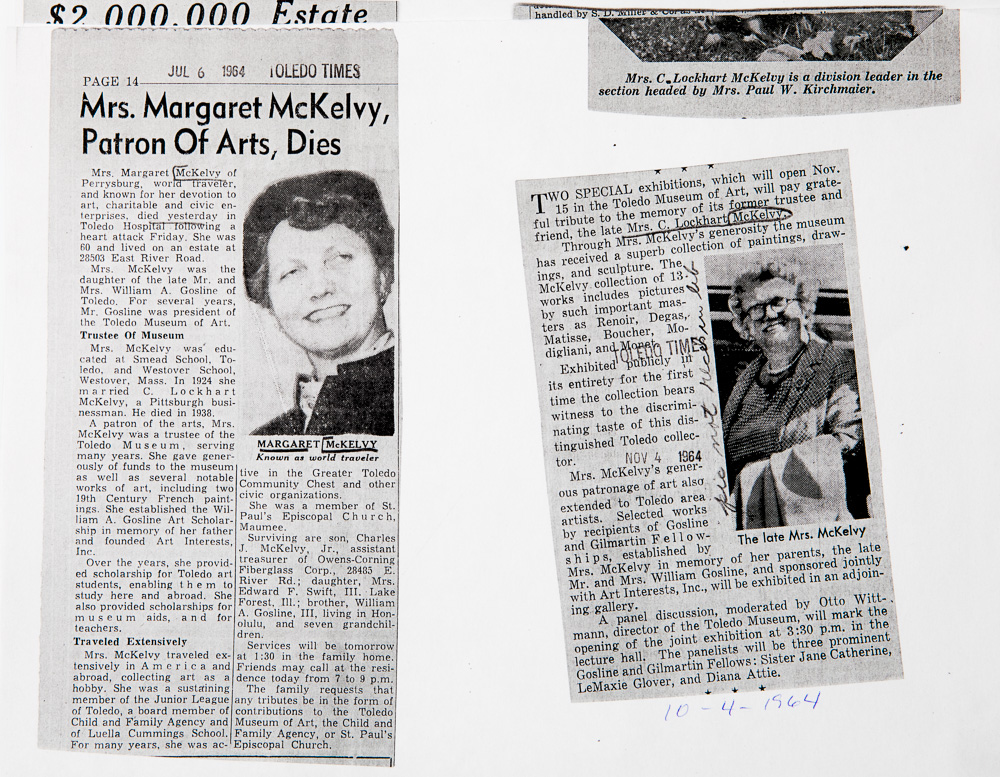

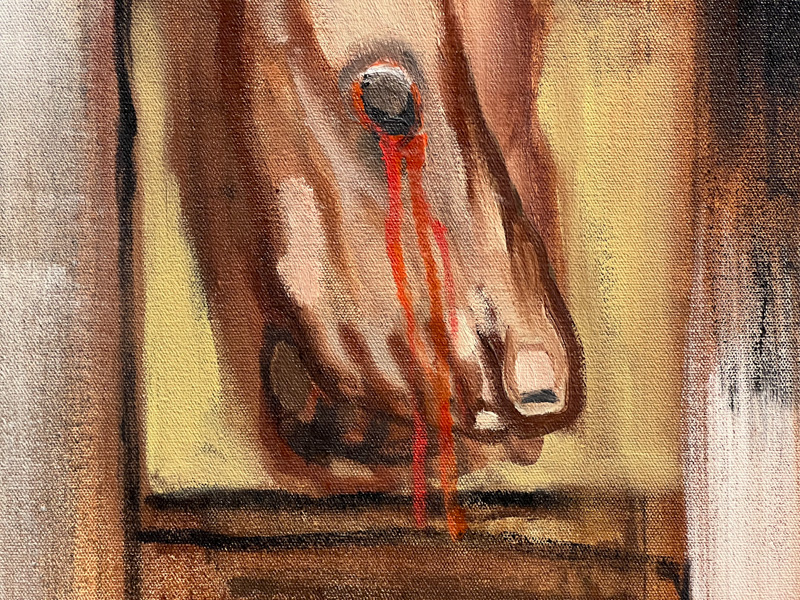

The commonality of LeMaxie Glover, Adam Grant, Carroll Simms, William H. Machen and their crucifixion artwork. clockwise from the top:

LeMaxie Glover, 1968 (1916 – 1984)

LeMaxie Glover made this crucifix for the baptistry at St. Richards Church in Swanton, Ohio. It is carved out of the finest walnut.

LeMaxie Glover was born in Macon, Georgia in 1916. His family moved to Toledo when he was small. He loved his art classes at Macomber and Libbey high schools. LeMaxie got married and had three kids, and supported them with a job working on trains. Art became his hobby. He took classes at the Toledo Museum of Art School of Design in the 1940’s. Encouraged by teachers and at the age of 34, he decided to become an artist.

One day Mrs. McKelvy, a wealthy woman and great supporter of the art museum, called LeMaxie on the phone and asked him if he’d like to study for a master’s degree at Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. He couldn’t, he said, because he had a family to support. So she offered to cover all of their household bills with a monthly check. LeMaxie received a scholarship to study at Cranbrook and earned his masters in 1956. That year, the Toledo Museum of Art gave him a one-person show. Offered a professorship at Cranbrook, he turned it down because he felt a strong need to give back to his Toledo community, since he was helped so much. He returned to Toledo and taught art at Woodward High School.

In 1968, amidst the heated-up racial tensions, he asked to be transferred to the inner-city Scott High School, where he could be of more help. 1968 is the year he was commissioned to carve this crucifix, which expresses the strength of Christ and the pain and suffering that Christ felt as he died on the cross.

LeMaxie Glover was a celebrated artist in Toledo. The Toledo Museum of Art was a major influence on him. He got his start with the serious art classes the museum once offered to the adult community. The museum’s most generous patron, Mrs. McKelvy funded his higher education. He showed in the Toledo Area Artists Exhibitions from 1956 to 1964, and in 1973 and 1974, in the museum’s Black Artists of Toledo Exhibitions. In 1970, his was one of the final Toledo Museum local artist solo shows (that had been stopped temporarily while the museum remodeled the back entrance, but then never resumed.)

One of the first to receive a Walbridge study grant from the Toledo Museum, LeMaxie Glover toured and studied at museums in Lisbon, Madrid, Rome, Florence, Milan, Paris, Amsterdam and London. He was a charter member of the Toledo Museum of Art Minority Advisory Committee.

LeMaxie Glover died in 1984 at the age of 67. He inspired generations of artists in Toledo, including Robert Garcia (who actually had the very last local solo show mentioned above, after LeMaxie Glover.)

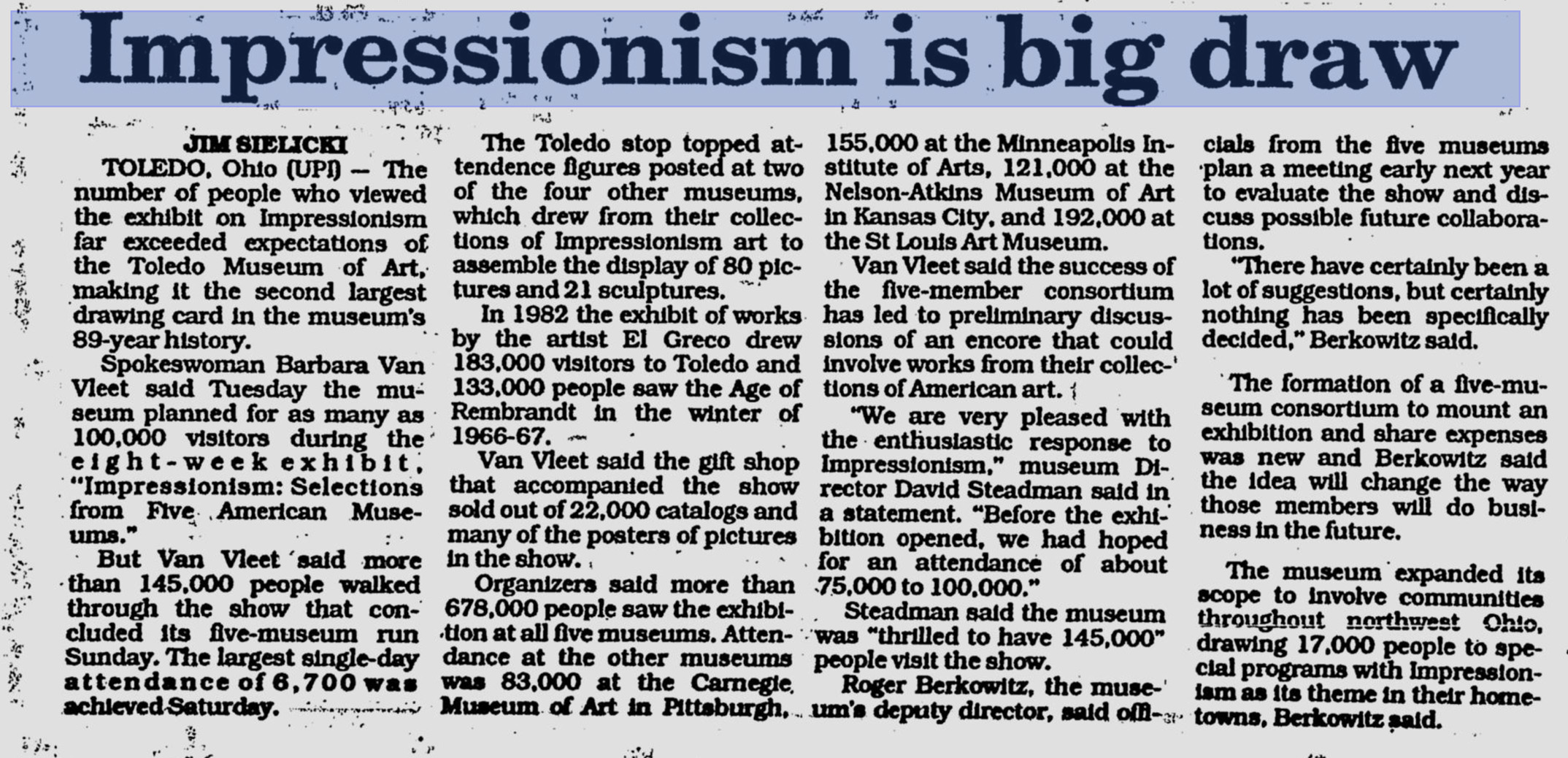

Adam Grant, 1976 (1924 – 1992)

Adam Grant painted this crucifixion in 1968 for the Corpus Christi University Parish in 1968. It hangs today in the chapel.

Adam Grant’s 2004 retrospective catalog begins with, “Adam Grant was born to be an artist.” It’s all he ever wanted. Born in Warsaw, Poland in 1924, he was a Roman Catholic, and he was a slav – a group victimized by Hitler.

In the fall of 1943, 19-year old Adam Grant was shoved into a train to Auschwitz, imprisoned, and later sent to the labor camp at Mauthausen, near Linz, Austria.

The 11th U.S. Army liberated Mauthausen on May 6, 1945. Adam Grant, extremely weak, very alone in the world, was taken to a camp for misplaced persons. Five years later Adam got himself to America, to Hamtramck, Michigan, where he connected with a creative community and resumed his art. There he got a job designing “Paint-by Numbers” kits and met his future wife, Peggy, who he married in 1954 and moved to Toledo.

The art of Adam Grant, who witnessed so much human transformation and experienced unimaginable pain, was concerned with the human form. The face of Christ that Grant painted is at peace, as if it is the moment that his soul left his body.

Adam Grant suffered from depression all of his life. He was a prolific painter who lived in Toledo. His work was shown internationally, including 33 times in the annual Toledo Area Artist Exhibitions, a solo show at the Toledo Museum of Art, and he was the recipient of a posthumous 2005 Toledo Federation of Art Societies Special Award. He died in 1992 at age 67.

The Grants loved the work of LeMaxie Glover. On their 6th wedding anniversary, Adam gave Peggy a sculpture of a torso made by LeMaxie Glover.

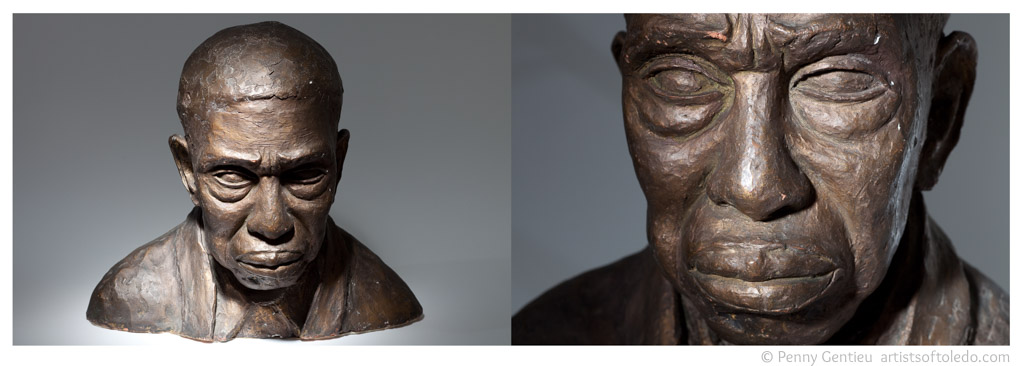

Carroll H. Simms, 1968 (1924 – 2010)

Carroll Simms made this bronze crucifix for St. Oswald Church in Tile Hill, Coventry, England. Titled Christ and the Lambs, it is hanging on the outside front of the church and is viewable from the highway.

Carroll Harris Simms was born in Bald Knobb, Arkansas in 1924, where his great-grandfather, a freed slave, was the first schoolmaster of Bald Knobb Special School for Negros. Carroll was inspired to pursue art from watching his grandmother make quilts. His first drawings were of locomotives and trains.

Hard times brought the family to Toledo in 1938, where Simms flourished and developed as an artist. In 1944 he received a scholarship to Hampton Institute, which opened his mind to the cultural richness of of African-Americans. He returned to the University of Toledo in 1945 and took art classes at the Toledo Museum of Art School of Design. From there, he received a scholarship to Cranbrook, funded by Toledo’s great art supporter, Mrs. McKelvy, who would a few years later do the same for LeMaxie Glover.

Simms graduated from Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1950. Staying close to Toledo during his formative years, he took part in an active museum-centered group of peer artists, A.R.T. He showed his work in Toledo Area Artist Exhibitions, where he won the Sculpture First Award for Mother Earth and Honorable Mention for The Workman in 1949. He won the Sculpture First Award again in 1950, and was rewarded with a solo show at the Toledo Museum of Art in 1951.

Carroll Simms lived in Nigeria for two years, not to study art but to soak up the culture. He was the recipient of two Fulbright scholarships to research West African art, in 1968 and 1971. He became a professor at Texas Southern University in Houston. Carroll Simms, together with artist John Biggers, whom he had known since the Hampton days, built the university’s art department from the ground up. Today he is known for his abstract sculpture linking to an African past. His public art is well-known in Houston and the world. He died in Texas in 2010.

Carroll Simms designed his crucifix without a cross, embodying it within the figure of Christ. The sculpture is modern, tribal and medieval, notable for the large hands, asymmetrical arms, foreshortened legs, resolute expression and wide open eyes.

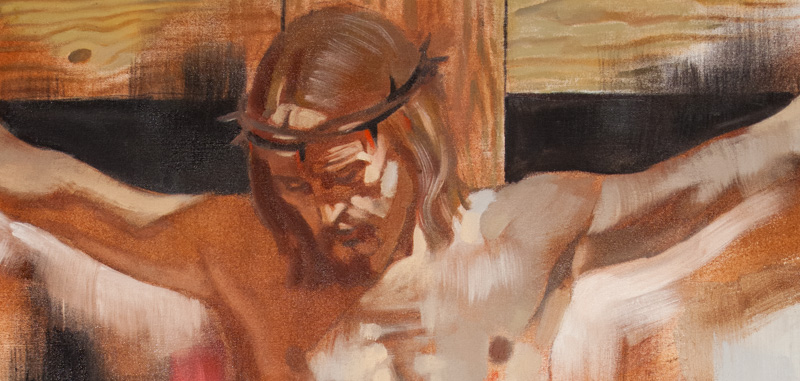

William H. Machen, 1869 (1832 – 1910)

William Henry Machen painted this painting of the crucifix for St. Francis Parish in Toledo, completing a set of the Stations of the Cross.

William H. Machen is Toledo’s first known artist. At the age of 15, he immigrated with his parents and siblings to Toledo from Holland, his family displaced by political exile of 1790’s France.

His grandfather, Constant De Besse (1762-1828) was a Girondist during the French Revolution. As Vice-Mayor of LeCateau (birthplace of Matisse) his duty was to arrest suspects, but he allowed Catholic priests to escape. For this he was arrested and condemned to death by guillotine. He bribed his jailer and, helped by two brothers who were revolutionists, he escaped and crossed the border into Germany. From Wesel he went to Holland where he changed his name to Machen, 1797. (This history written on the family tree.)

William Machen was the “first artist to recognize the beauties and traditions of Northwest Ohio, and to give them a certain dignity and purpose,” making paintings that show us today what Toledo looked like in the very beginning, and even before. He was 20 when he made his first entry in the journal he would keep of all the paintings he made throughout his life. A devout Catholic and organist for St. Francis Parish for 31 years, he painted the Stations of the Cross for the church.

In 1931 a fire nearly destroyed the paintings. The smoke and fire damage to the paintings was treated with a poor restoration, which further damaged the paintings. In 2007, the paintings were crated and stored in the church to await their fate.

William Machen’s great nephew, Jim Machen, hired me in 2012 to photograph the paintings. I put them on my website, and together we tried to elicit support for their restoration. After exhausting all possibilities of support and enduring other disappointments, Jim died in 2020.

Just one month later, the story of the paintings on my website was discovered by an architect who was renovating a church east of Toledo in Genoa, Ohio. Then on Good Friday, 2021, I was commissioned by the priest to digitally restore and print on canvas the stations, using my high quality photographs taken in 2012. What a privilege. I spent days working on each one, so I know what it is like to contemplate and closely witness, as both an artist and a human being, the crucifixion of Christ.

William Machen did not thrive in Toledo, having lived in the city before the art museum was built. He missed the symbiotic relationship that developed between the museum and the local artists. Machen left in 1882 for Detroit where he found more support as an artist. Ironically, he left Toledo right before other artists, such as Parkhurst, Stevens, and Osthaus coming to Toledo were to form the club that was to create the Toledo Museum of Art. Machen eventually moved to Washington DC and died in 1911, seven months before the young Toledo Museum of Art opened the doors of their beautiful new marble building.

William Machen’s work has always been overlooked by the museum. Even when the museum had their recent show about the War of 1812 in 2013, and another in 2015 about artists and the Civil War, the museum did not include Machen’s paintings, which would have enhanced the shows and told our story as a community. (See here) Neither Jim Machen nor I were able to make an appointment with the museum when we were seeking advice about the state of disrepair and possible restorations of the original Stations of the Cross paintings. That’s because William Machen was born too early, and I was born too late. The museum-nurtured Toledo art community that lasted for over 100 years was in the process of getting severed by the corrupt ending of the Toledo Area Artists Exhibition when we attempted to seek their advice.

William Machen was a scholar, musician, artist, linguist, writer and faithful son of the Catholic church – an immigrant who tried to make his home and art in Toledo. His body was returned by train to Toledo in 1911 and buried under a modest marker in Calvary Cemetery on Door Street, just a few feet away from the 2-mile radius border of the Adam Levine Toledo Museum of Art.

The four artists have many things in common — each one moved to Toledo for a better life, each one has a train story, and each one expressed through their hearts and souls the crucifixion of Christ. Three out of four had a lot of help from the Toledo Museum of Art, really enhancing their lives on this Earth.

You have to wonder, why has the Toledo Museum of Art forsaken the artists of Toledo?

For money and politics – The Toledo Museum of Art sold out the community for the grants.