An assessment of the offerings at

Adam Levine’s Toledo Museum of Art

two years into the five-year plan

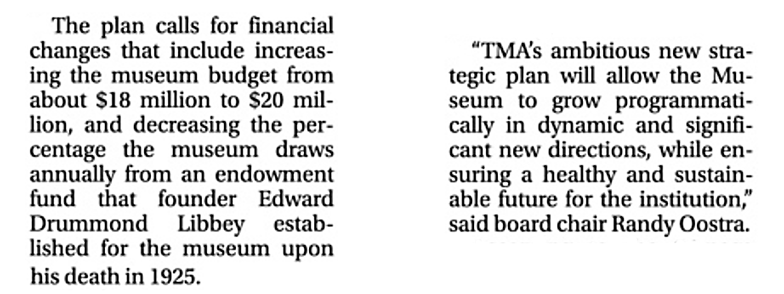

In 2021, Adam Levine, the new director of the Toledo Museum of Art, announced that he was increasing the museum’s annual budget by $2 million while reducing the draw from the Libbey Endowment. The rules of the Libbey Endowment are such that the money must be used in whole or in part for the exhibition of art, with at least 50% of every dollar spent on the purchase of works of art for the purpose of public exhibition. To draw less from the Libbey Endowment means they are free to do what ever they want. They don’t need to buy art or have great shows anymore.

Just as we had been warned, the shows since then have been sparse and less spectacular. We’ve had Matt Wedel, regional mid-career ceramicist, and his “Phenomenal Debris” filling up the Levis Gallery Nov. 5, 2022 — Apr. 2, 2023, which, as the name suggests, was a real departure for the Toledo Museum of Art, and not in a good way. Meanwhile in the Canaday Gallery, in a redo of a show from two years ago, they decked out the Canaday with artwork in need of repair and solicited donations for the restorations, for the privilege of the donor’s name being briefly associated with the “adopted artwork.” The piece used in the promotion was a 1925 glass dress, representing Libbey himself, ironically, to raise money for restoration instead of using the museum and Libbey’s money to restore the dress. So tacky of them. The show was up an extra-long time, from Sept 24, 2022 to Feb. 5, 2023. Now they give us a show about astrology and fortune-telling curated by the two new Brian P. Kennedy Leadership Fellows (formerly known as Mellon Fellows) who drew from the museum’s own collection. Feb. 3, 2023 — Jun. 18, 2023, because that is just what they think we like, after we endured the Supernatural traveling show in 2021.

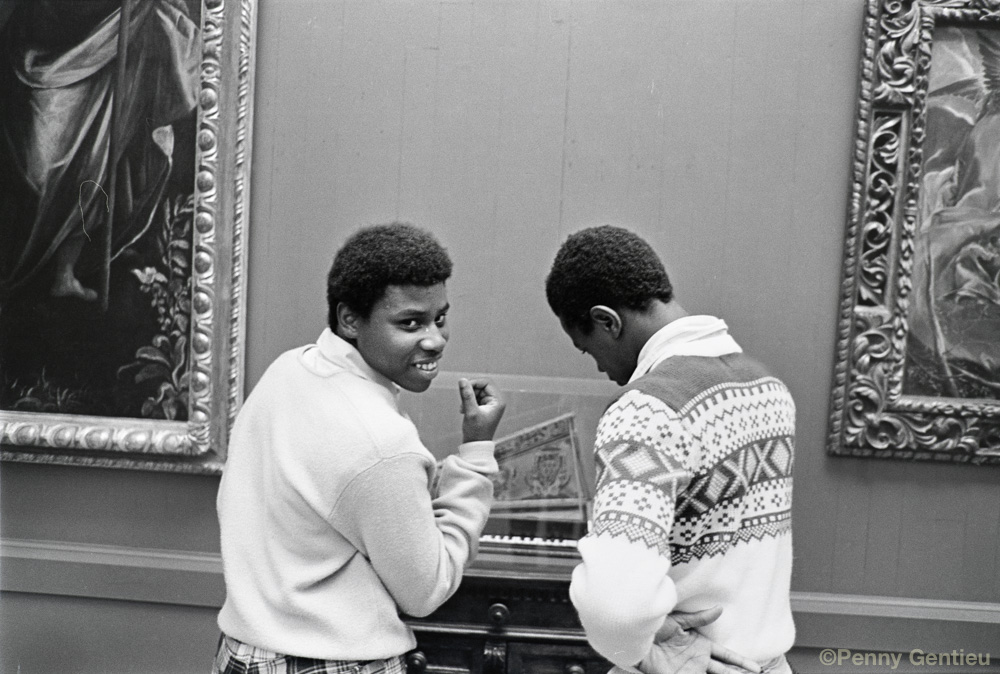

Meanwhile, as evidenced by features in the sporadically published Art Matters Magazine and nearly every press release Levine manages to put out, they go on and on about their curatorial work writing wall text and rearranging galleries, as if they are preparing us for a terrible fright. Lately, they have been moving art around in the American galleries so that the artworks will talk to each other and tell us the TRUE meaning of being an American. Because, as they tell us, being an American changes all the time, and you need to listen to the paintings, look closely and see how they interact. Do they like each other? Can they get along? If you still don’t get it, read the wall text.

But coming to Toledo this summer just in time for Juneteenth is the enthusiastically inspired traveling show called Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club, June 3 – Sept. 3. It is co-curated by Brooklyn Museum’s young up-and-comer Kimberli Gant, who wrote an accompanying book about the Black American artist (1917–2000) and the 1960’s Nigerian art scene. Read about Jacob Lawerence here on this unrelated time-capsule of a website from the Whitney Museum in 2002, too good not to share.

It is interesting that it is Kimberli Gant’s family who originally owned the burnt miniature American flag piece that the museum acquired last year, purchased with funds from the bequests “by exchange” of dead patrons who happened to have been veterans who fought under the American flag in World War II. Would these Toledo veterans have approved of their money being used to buy a burnt flag? I bet it would break their hearts. The burnt American flag to-date has not been displayed to the public. But the wall text has been written – with great enthusiasm.

Will the museum be showing the burnt American flag piece? Or is it reserved for their “programs,” as the museum’s curator of contemporary art mentioned on Instagram? It must be exciting for the underpaid “contracted” museum teachers (mostly women who are not given health insurance) to pull out this 8×10 burnt American flag painting mounted on a 4-ply museum board and use it to inspire both young and old people at the “outside the museum walls” art-making spaces in federally funded housing projects.

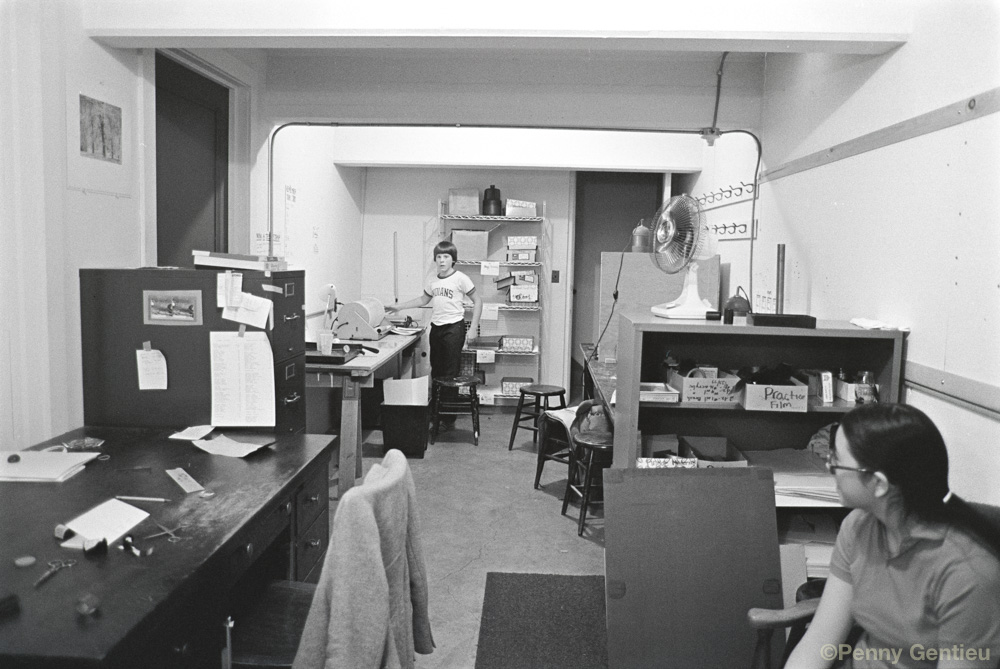

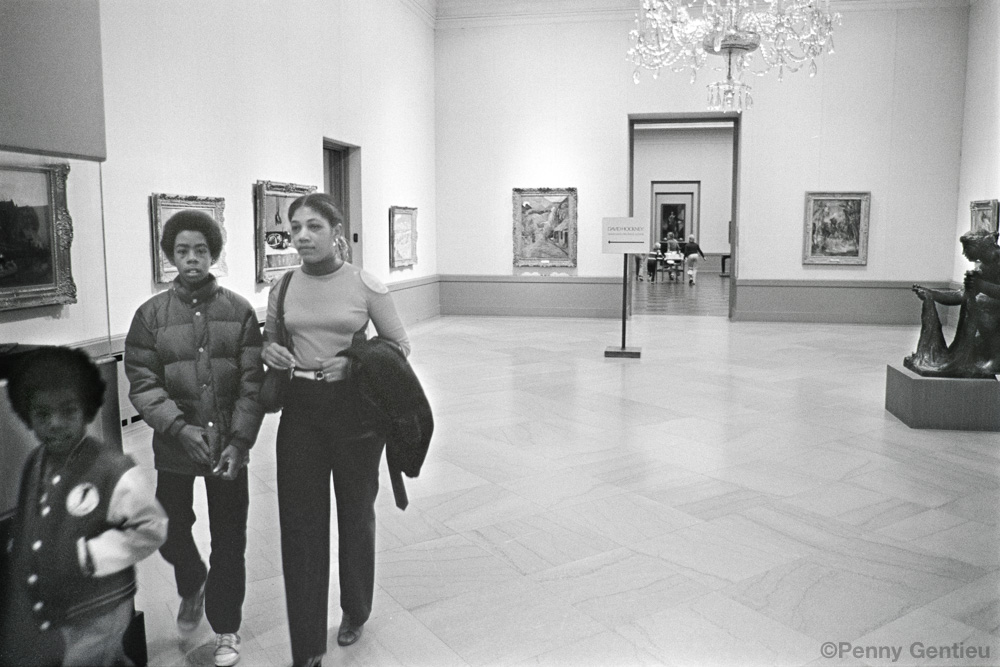

The art-making spaces are funded by a local manufacturer of fiberglas insulation and roofing materials, Owens Corning, and the program is run by the Toledo Museum of Art. Since the museum no longer has their long-time Children’s Saturday classes that took place in the basement of the museum, in a school aptly named The Toledo Museum of Art School of Design, bringing together 2,500 children from all over the city of Toledo every Saturday during the school year, not to mention the many hundreds of adults it served during the week, and now the halls are empty, Adam Levine likes to boast that they have burst “outside their walls” with this new program that serves 18,000 people in housing developments within a 2-mile radius of the museum. Whether the residents want it or need it or like it or not. Everyone else in the city is out of luck because most of their efforts are funneled into the Lucas Metropolitan Housing Authority, the President and CEO of which, Joaquin Cintron Vega, happens to be a new museum board member, along with Brian Chambers, the CEO of Owens Corning who is also on the board, sitting pretty.

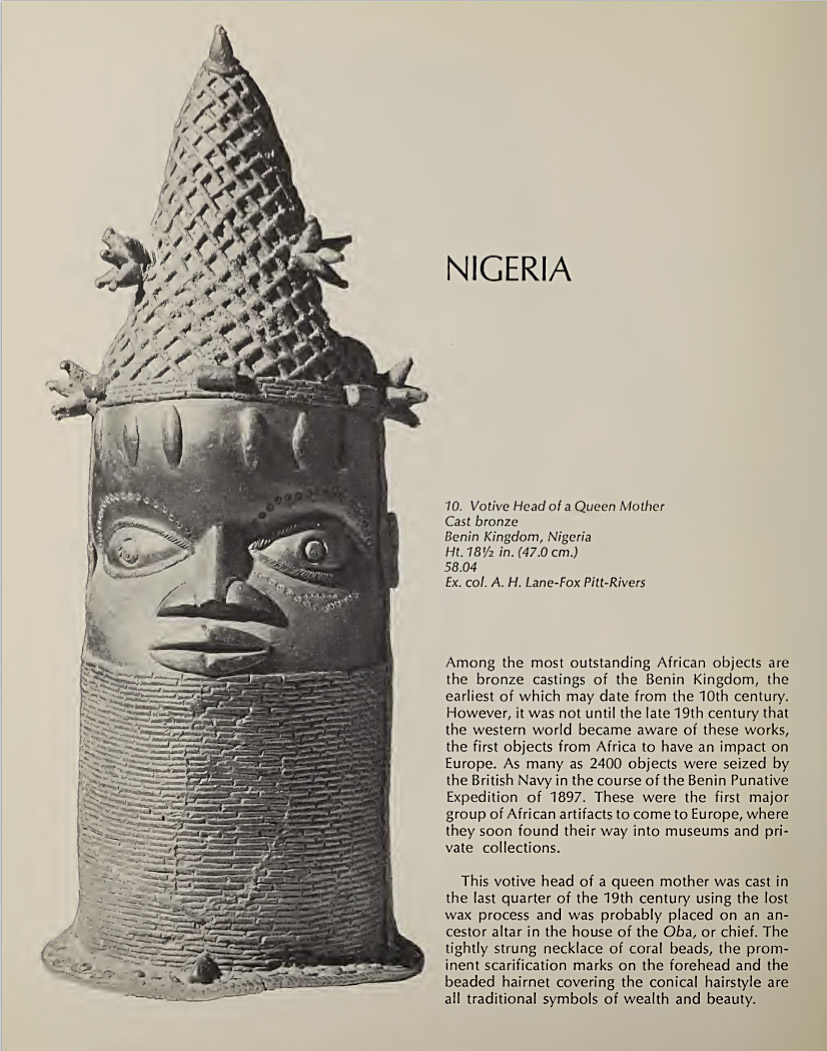

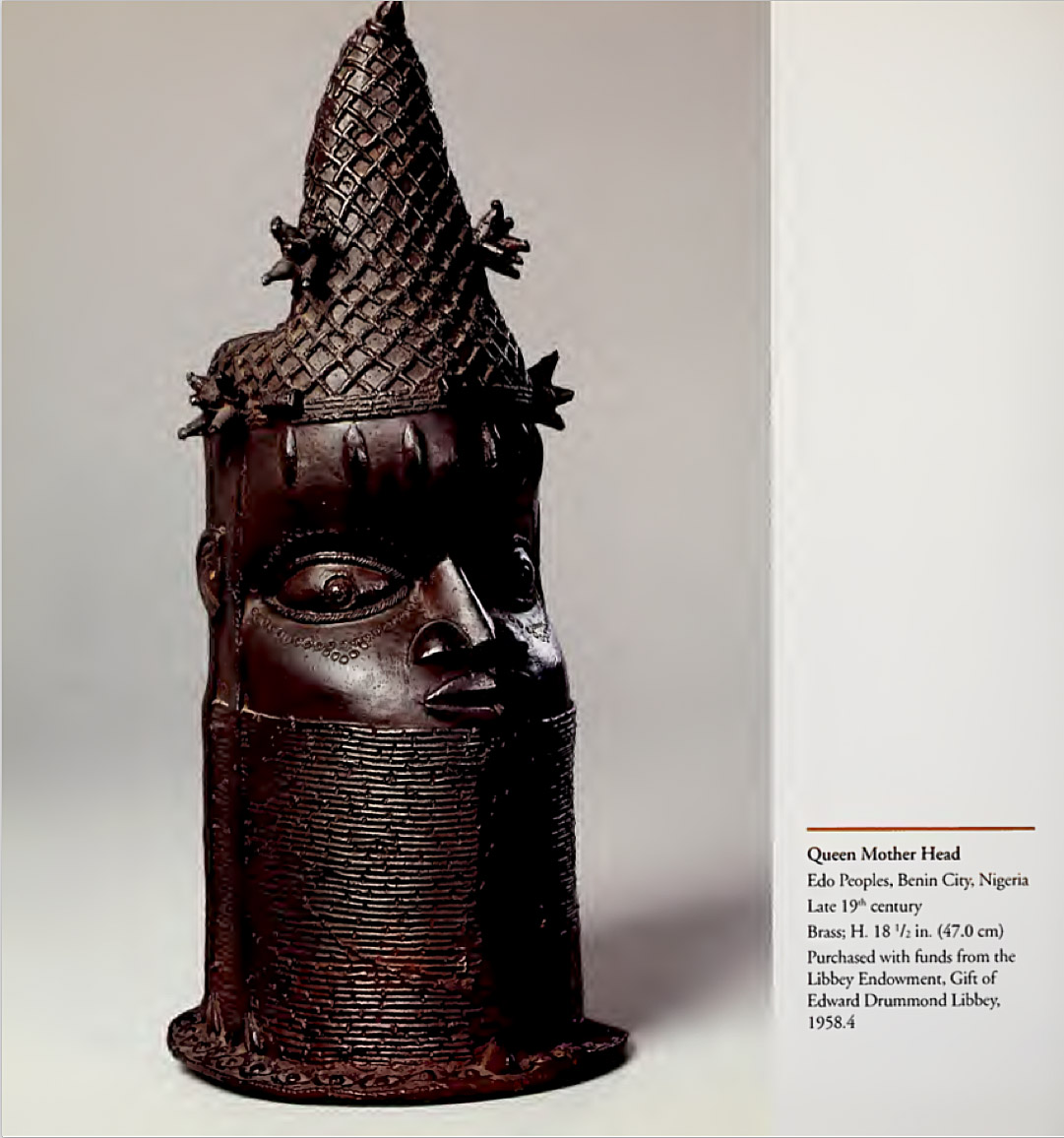

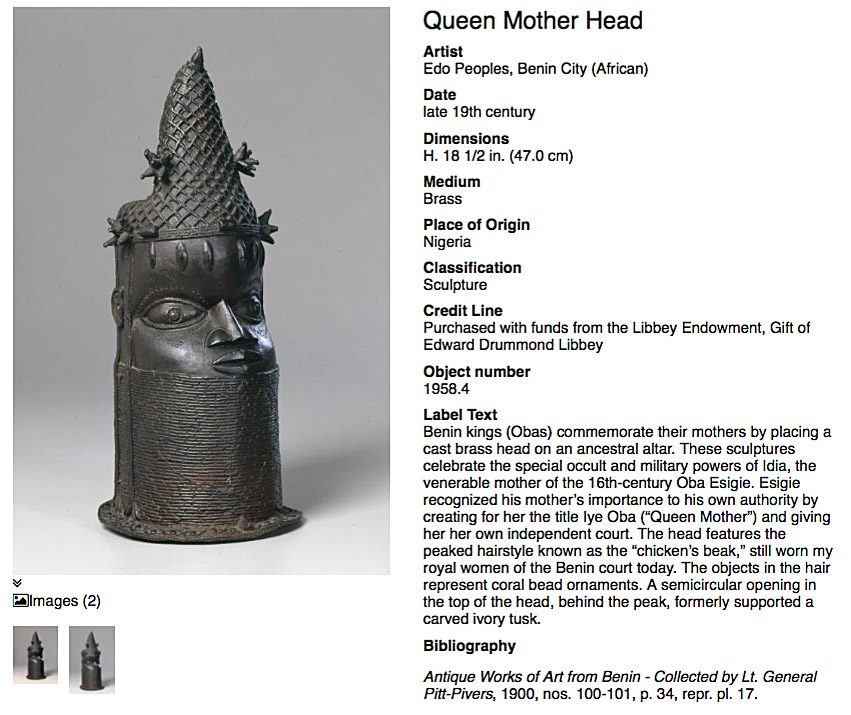

And speaking of Nigerian art, I wonder if the Toledo Museum of Art will be returning their looted Benin Bronze, or are they waiting out the storm, keeping it hidden while conscientious museums across the country are returning their looted art to Africa? Adam Levine must have figured that sooner or later the reports of returned looted art will be old news and used to wrap fish.

If we can only be patient, coming next year will be a show curated by the recently retired Toledo Museum Curator of European Art, Larry Nichols.

It was good timing that Larry Nichols retired right before the $59.7 million sale of the three French Impressionist paintings, two of which were sold to one buyer under suspicious circumstances. And now he’s back on a freelance basis, with a real show to help out the museum since they have not been able to come up with a good one on their own after hiring countless curators. (It’s not that they can’t, they just haven’t wanted to.) There will be a show with not just one, or two, or three, but four Caravaggios, and they will be conversing with the wanna-be Caravaggios in the museum’s collection. How exciting! Put it on your calendar — Jan. 20 – April 14, 2024. I can’t wait!

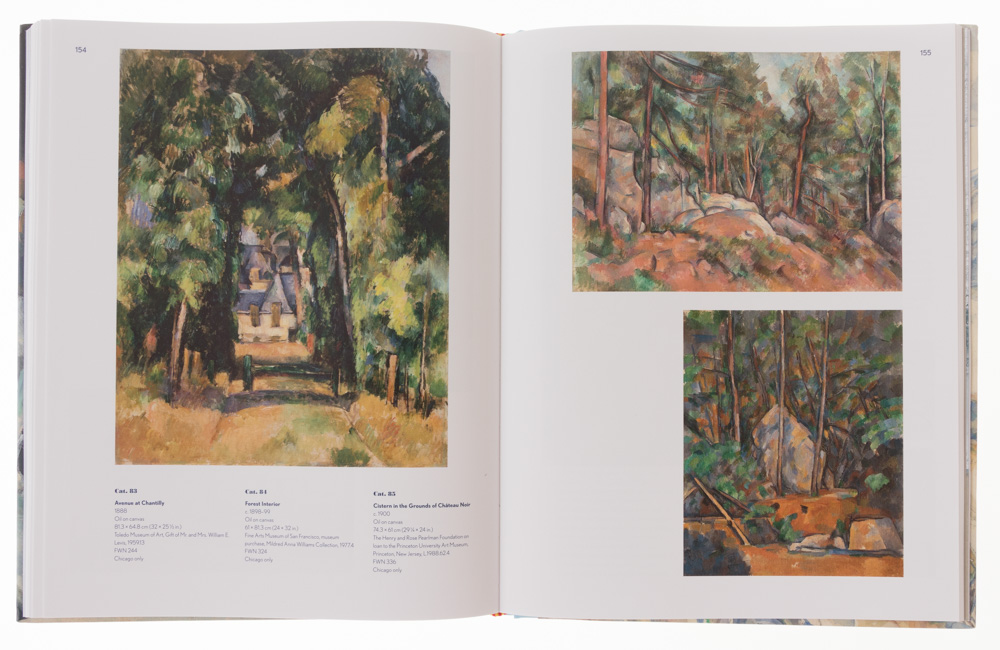

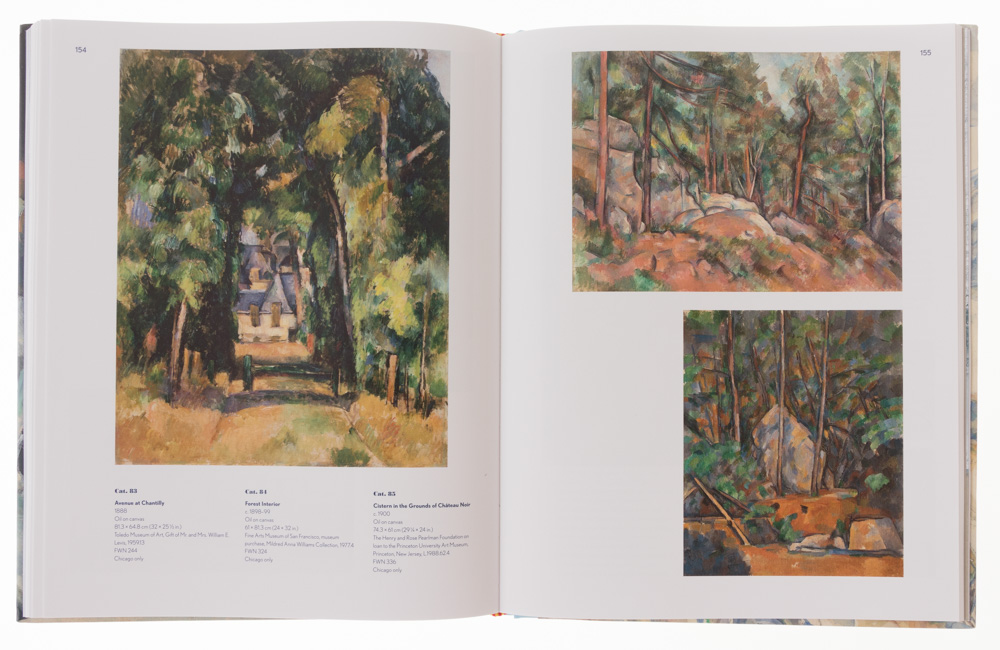

I’m glad the museum could give our venerable old art curator an outlet during his retirement. Somehow Larry Nichols managed to persuade four museums to trust the Toledo Museum of Art, to get the museums to loan to Toledo their valuable painting. What a lucky break after the Toledo Museum of Art reneged on their promise to loan our Cezanne Avenue at Chantilly to the Art Institute of Chicago for their major Cezanne exhibition, which opened two days before our museum sold at Sotheby’s our valuable Cezanne painting, The Glade to a secret buyer for $41.7 million, the same mysterious person also buying Henri Matisse’s Fleurs ou Fleurs devant un portrait for $15.3 million. (See page in the show’s catalog, Cezanne, that was printed right before the show.)

What was the hurry to sell our paintings? Was our collection used as a catalog by a collector who made an offer that had a time limit that made Adam Levine betray his commitment to the Art Institute of Chicago? How could Adam Levine have sold our Cezanne right out from under these circumstances and break a promise to an esteemed museum? It hurt the exhibition, it hurt the public, it hurt the historic record, it hurt our institution – it hurt everyone. It is his fiduciary duty to be a good steward and to honor the reputation and legacy of the museum.

The money from the sale of the French Impressionist paintings, the Cezanne and Matisse that came from the Libbey Endowment and the Renoir that came from Mrs. McKelvy’s French Impressionist collection, should have been spent immediately on art, or else it should have gone back in the respective endowments. But instead they started an entirely new financial instrument with the proceeds of the art, making a lot of money for the bankers.

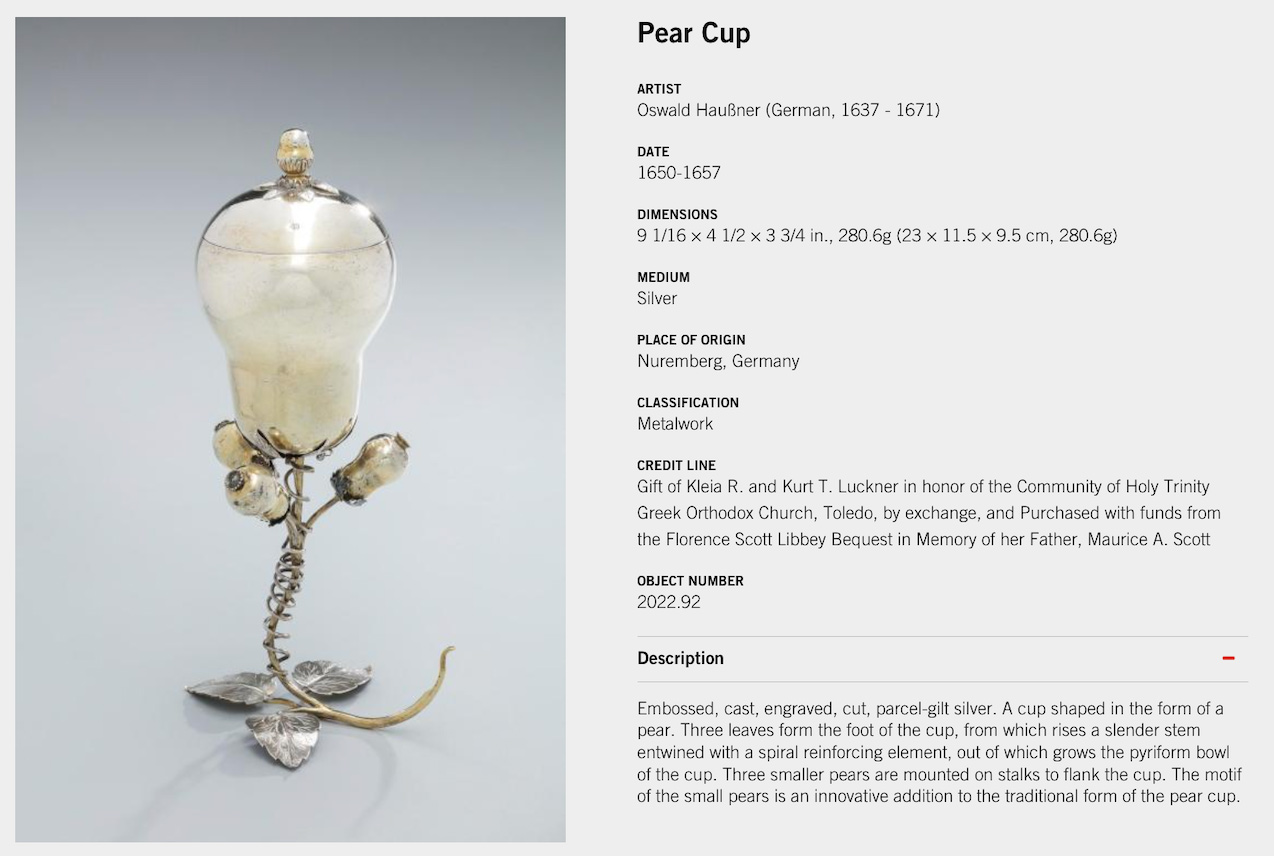

I wonder what the $2 million per year increase in the museum’s annual budget is going toward? They hired two people to be in charge of “People” and “Belonging” (a Chief People Officer and the other is the Director of Belonging.) The shows, as noted above, have been bare minimal offerings. They’ve reduced their public education to a skeletal existence. They closed the museum on Tuesday as well as Monday (except for MLK Day, a new tradition), so it is now only open five days a week. They raised their parking fee by 45%, right after they sold the museum’s three famous French Impressionist paintings. There are huge gaps in acquisition numbers for the art acquired in 2022, keeping the public from finding out what they are buying. This, after they made such a big deal about what they were going to buy. As it is a public institution formed to exhibit art to the public – the public has a right to know.

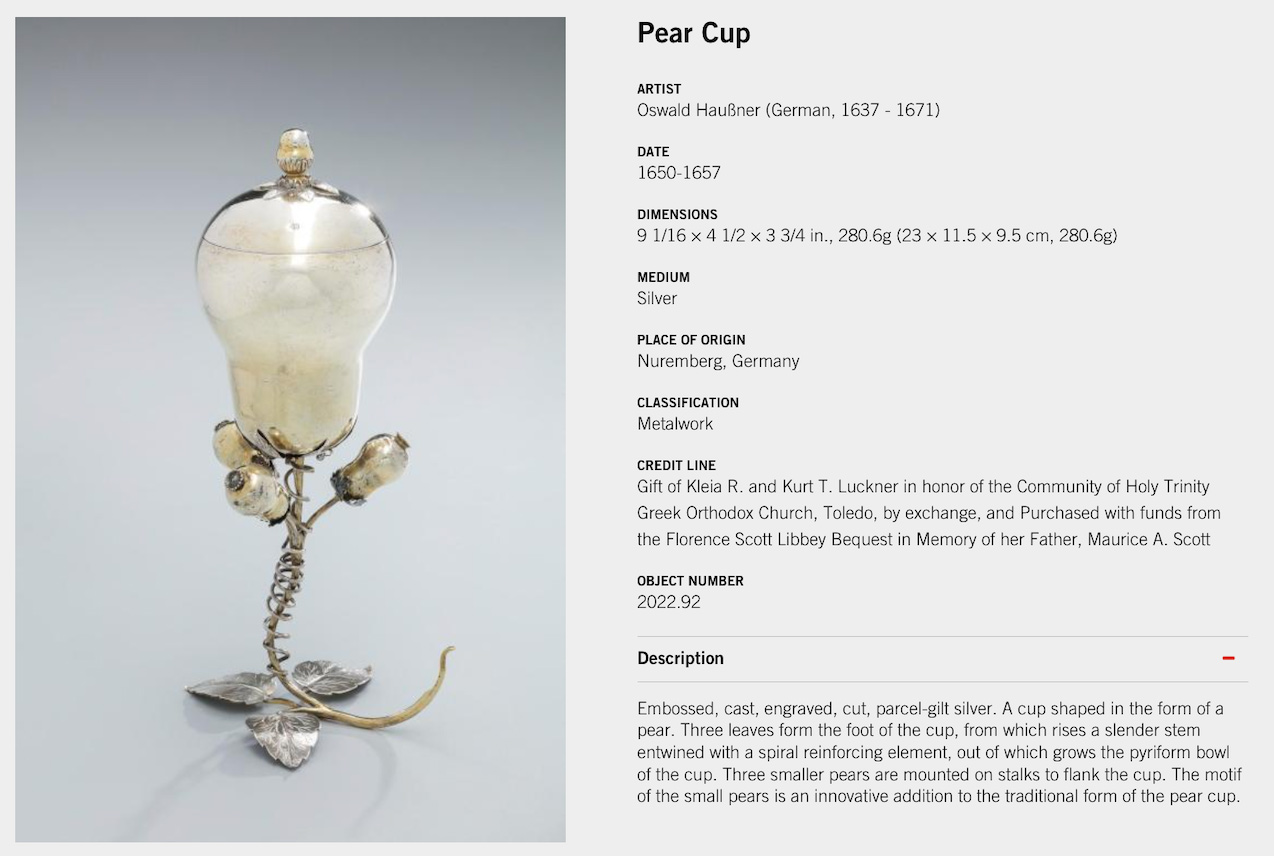

Why did the museum hire a curator of ancient art, Carlos Picon, the director of the Colnaghi art gallery in New York, who is an ancient art dealer? Isn’t that a conflict of interest? Do the objects being bought now really speak to the museum’s so-called mission of collecting art that looks like us and are they filling in cultural gaps and expanding the narrative of art history? Or is it the same old fluffy stuff?

Adam Levine said in his 2022 Forbes interview for a feature story on beauty without bias, “The superpower that an art museum has is when something goes up on the wall, it’s considered good. We set the cannon.” They’ve got the power, and they can do whatever they want with it.

In June 2021, the museum announced that a new gallery was being renovated that would be exclusively for solo shows of local artists. Then there was dead silence about it. It never materialized. After a year and no gallery, the donor himself, Bob Savage, told me that it was delayed because the museum couldn’t decide what to do. That’s how much they regard the local artist community, as if we do not “belong” or fit into their community/people/belonging plan. Then last week, on February 23, very quietly, Ohio’s Ninth Congressional District Invitational Art Competition high school art show opened the new gallery. No announcement of the gallery or the event was made to the public or to the artists of Toledo, but Ohio Congressman Marcy Kaptur, Representative of the Ninth Congressional District, was at the high school area art event named after her district thanking donors Sue and Bob Savage. So much for local adult artists as politics takes center stage at Adam Levine’s Toledo Museum of Art.

I remember writing to the museum board two years ago when their five-year plan was published in The Blade (see the first Blade article on this post). I wrote in response to the renewed community focus, and could they please bring back our 100-year old Toledo Area Artists Exhibition? The response was favorable and and Randy Oostra, the CEO arranged for me to have a meeting with Adam Levine, which took place two months later. That day, ready to give my spiel, Adam Levine surprised me with news that he said I would be the first outside of the museum to know – that they were renovating a gallery specifically for solo shows for local artists. One month later The Blade featured a news story (see above) a with a photo of Adam Levine, the donors that will pay for the renovation, and the mayor of Toledo. Then not a word was ever spoken or written about it, not on their website nor in social media, nor in their members magazine, then one mention, occurring in The Blade one year later in regard to the art making spaces in the federal housing projects, that those new art-makers may have a show at the museum gallery. Finally, nearly two years later, the gallery that was promised to professional local artists opened with a show for high school students. I feel sorry for those young artists because when they grow up, they will get no support from the museum, unless they live in the projects.

When the museum talks about community, local artists are not included. The art museum makes their own artists now.

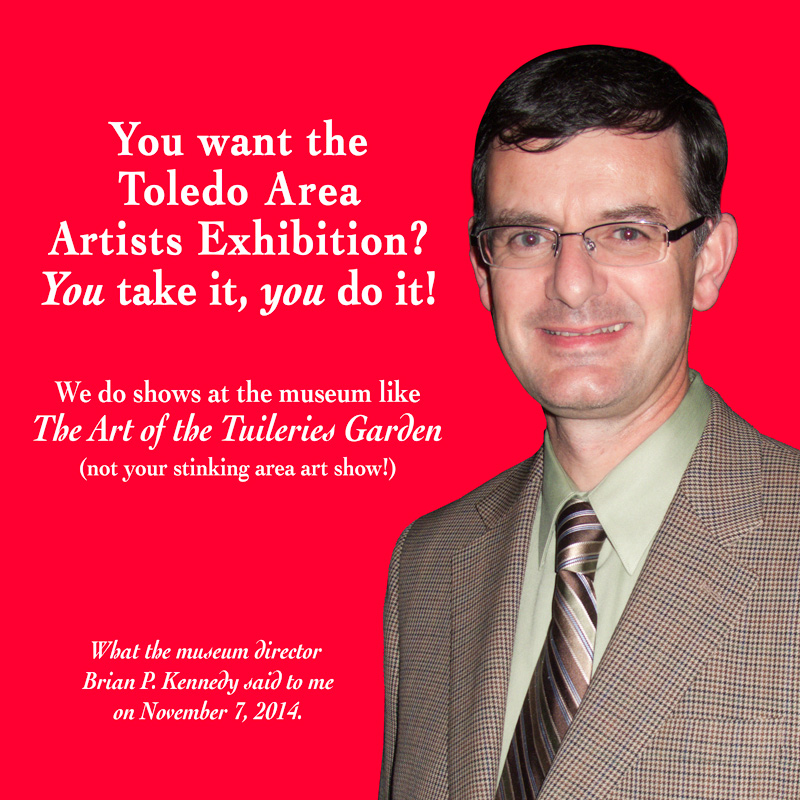

We must trust them and believe they have our best interests at heart, Leslie Adams assured us in 2014. The former president of the Toledo Federation of Art Societies got a one-person show from the museum in 2013 as the first, and as it turned out, the only, biennial solo show prize winner ever. Other TFAS former presidents and museum insiders were also rewarded when the museum corruptly abruptly canceled our prestigious Toledo Area Artists Exhibition that we had had for nearly 100 years.

It is a tragedy for the community that the Toledo Area Artists Exhibition was ended. For nearly a century, it helped countless artists achieve their goals, including three generations of my family. Check out the significance of the show by looking at the bios, clippings and obituaries of the many historic Artists of Toledo on this website. The shows played a prominent role in the careers of nearly every successful artist in Toledo. The demise of this annual show hurts our very DNA.

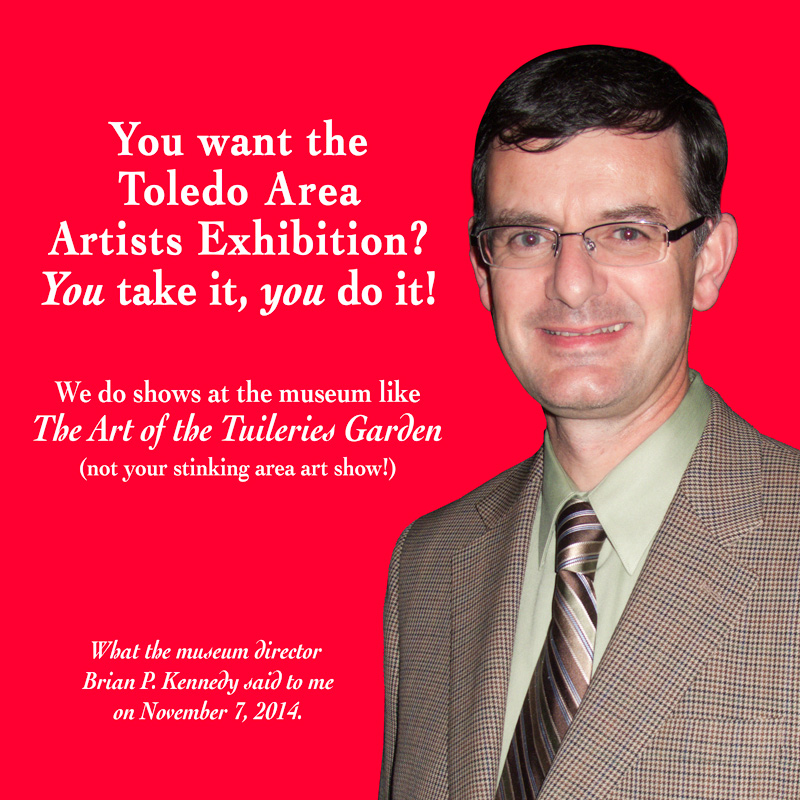

Brian P. Kennedy, director from 2011 to 2019, is oddly honored. The Mellon Fellow title has been renamed to “Brian P. Kennedy Leadership Fellow.” It’s too bad that one of the first two Mellon Fellows hired by Kennedy (Halona Norton-Westbrook) was involved in the corruption of the Toledo Area Artists Exhibition in 2014. It gave the Mellon Fellowship a bad name. But with the new name, what kind of role model for leadership is Brian Kennedy after he resigned from the Toledo museum just 18 months before the end of his 10-year contract to go to the Peabody Essex Museum, then he quit that museum after only 17 months? Of his leaving the PEM, Kennedy said:

After thirty years in museum leadership on three continents, this current unprecedented period of racial, social, economic and political turmoil has given cause for serious thinking and new perspectives on the profound changes that are happening in our world and I have decided to pursue a new challenge.

Which is extremely weird.

His departure caused a great deal of damage to the Toledo Museum of Art in 2019, because the museum was not prepared with an heir apparent. It led to the unfortunate situation we are in today. The board members ended up hiring the museum’s other Mellon Fellow hired by Kennedy – Adam Levine – who had left Toledo, but then came back for this. But after just a couple of years and this track record, what is going on?

The museum has traded connoisseurship for money and politics. Art can be political, but a public art museum cannot be, because that would be divisive and polarizing. The Toledo Museum of Art was built on the principle of community.

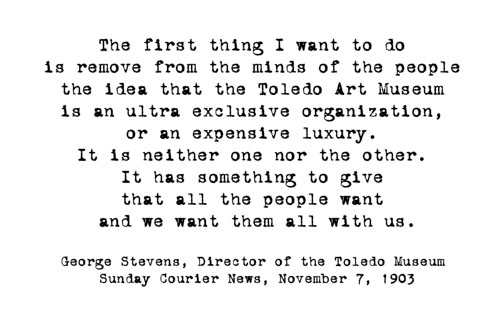

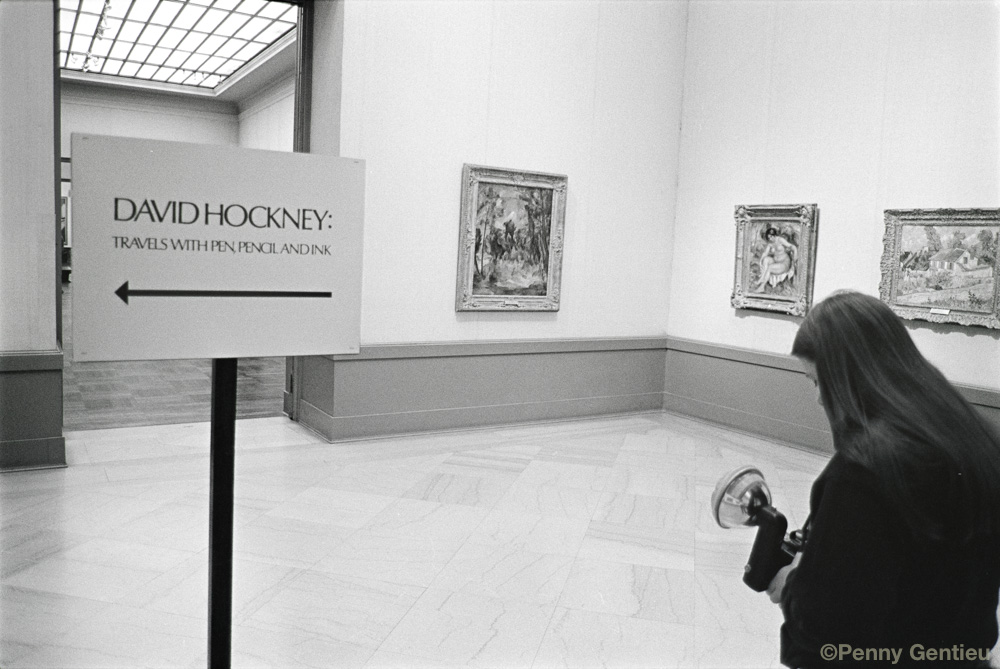

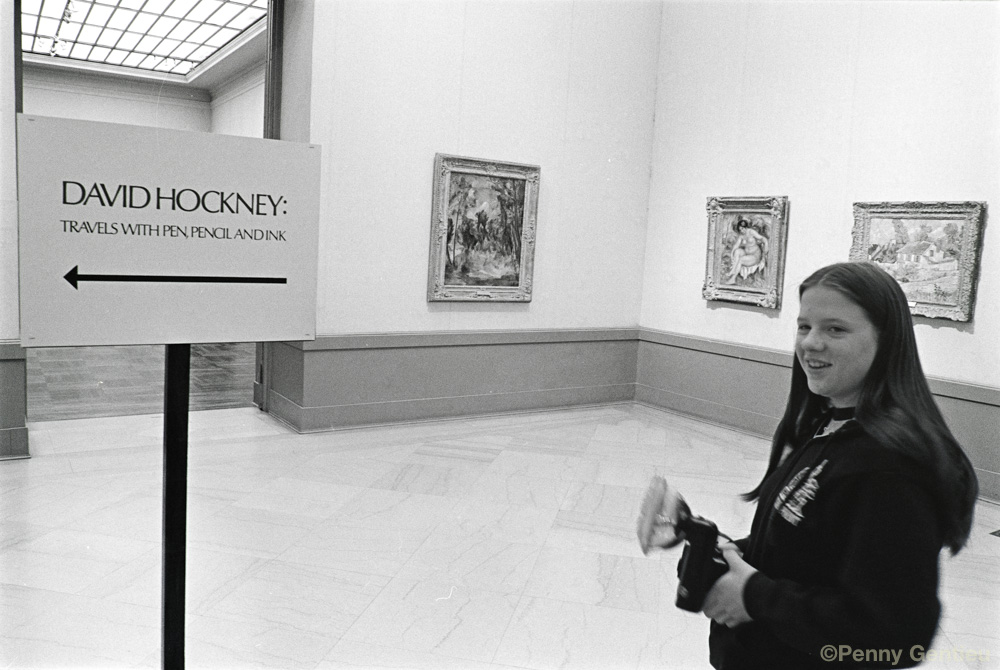

In summary, our museum was built with wide open doors inviting everybody to walk through them. Before it was reduced to a bare minimum, the museum had the best educational system of any museum in the country, serving every person in the entire city who had a desire to learn about art. It was the hub of a robust local artist community that for many years had monthly local shows, and for 95 years had the prestigious annual juried show for local and regional artists. Not to mention the great art collection.

The art collected by the museum was chosen by art connoisseurs for its quality and encyclopedic representation of the world, as opposed to now, where it is chosen to serve a political agenda or fill a quota. From early-on and throughout the past century, our museum had been highly respected and drew great leaders such as Otto Wittmann and Adam Weinberg. The museum always had many shows going on at once and events of public interest. They published newsletters, catalogs and magazines keeping the public informed of all their goings on.

The museum’s mission was to educate and exhibit art to the public.

Today the mission seems quite vapid. That is, to get other museums to notice us and want to be like us. “THE MUSEUM SEEKS TO BECOME THE MODEL ART MUSEUM IN THE UNITED STATES FOR ITS COMMITMENT TO QUALITY AND ITS CULTURE OF BELONGING.” Yet how do we look to other museums when promises are broken? It is hypocritical to appear so “woke” while holding on to a Benin bronze looted art, not exhibiting it, not sending it back to Nigeria, and not a word about it one way or another. Their mission statement reveals their emptiness and hypocrisy, just like their new ad slogan “Art brings Toledo together,” when it’s doing quite the opposite.

The museum should be serving all the people who live here. Local artists matter. Our museum should not be used as a social experiment or as a stepping stone for the director’s next career move. But then it all seems like a smokescreen while they sell our valuable and beloved paintings, and who is profiting from that? Just look at everything that is at stake – artwork that is worth billions collected over 120 years.

With their two million dollar increase in the annual budget for the past two years, they have so much less to show for it.

It’s OUR museum. Where is the oversight?

Who gave them the right to take away the fundamental qualities of our museum, sell our art, demean our founders, kill our local traditions, invade our museum, live off our stellar reputation like blood-sucking vampires, and take our museum in a new direction all their own? Who are these people?

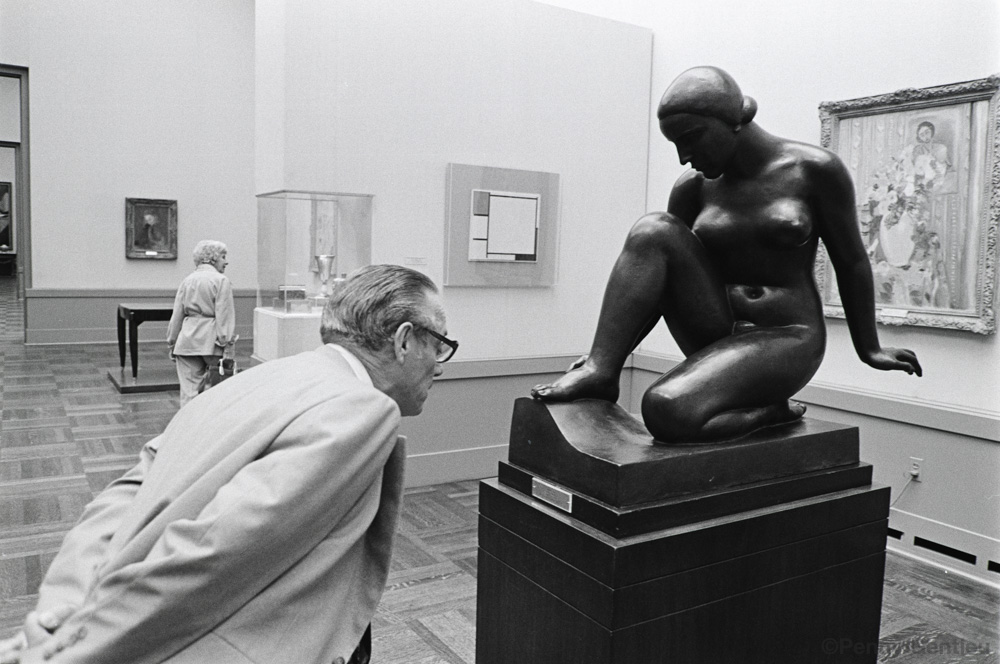

After leaving the first gallery, where the Cezanne and Renoir paintings were shown prominently, a visitor would enter the next gallery, where one of the first paintings in the gallery hanging on the right would be Henri Matisse’s Fleurs ou Fleurs devant un portrait that Adam Levine also sold. Here, a visitor examines a sculpture by Aristide Maillol (1861-1944), Le Monument à Debussy, (in conversation with the Renoir sculpture in the first gallery) with the Matisse painting hanging in the background.

After leaving the first gallery, where the Cezanne and Renoir paintings were shown prominently, a visitor would enter the next gallery, where one of the first paintings in the gallery hanging on the right would be Henri Matisse’s Fleurs ou Fleurs devant un portrait that Adam Levine also sold. Here, a visitor examines a sculpture by Aristide Maillol (1861-1944), Le Monument à Debussy, (in conversation with the Renoir sculpture in the first gallery) with the Matisse painting hanging in the background.