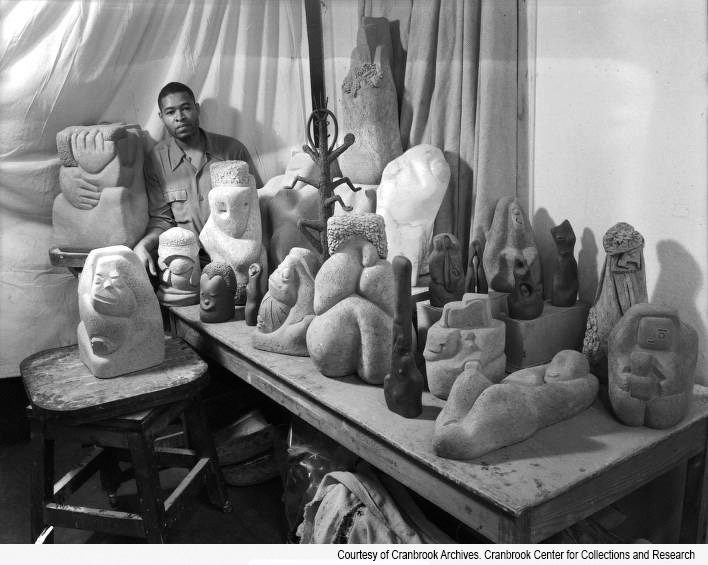

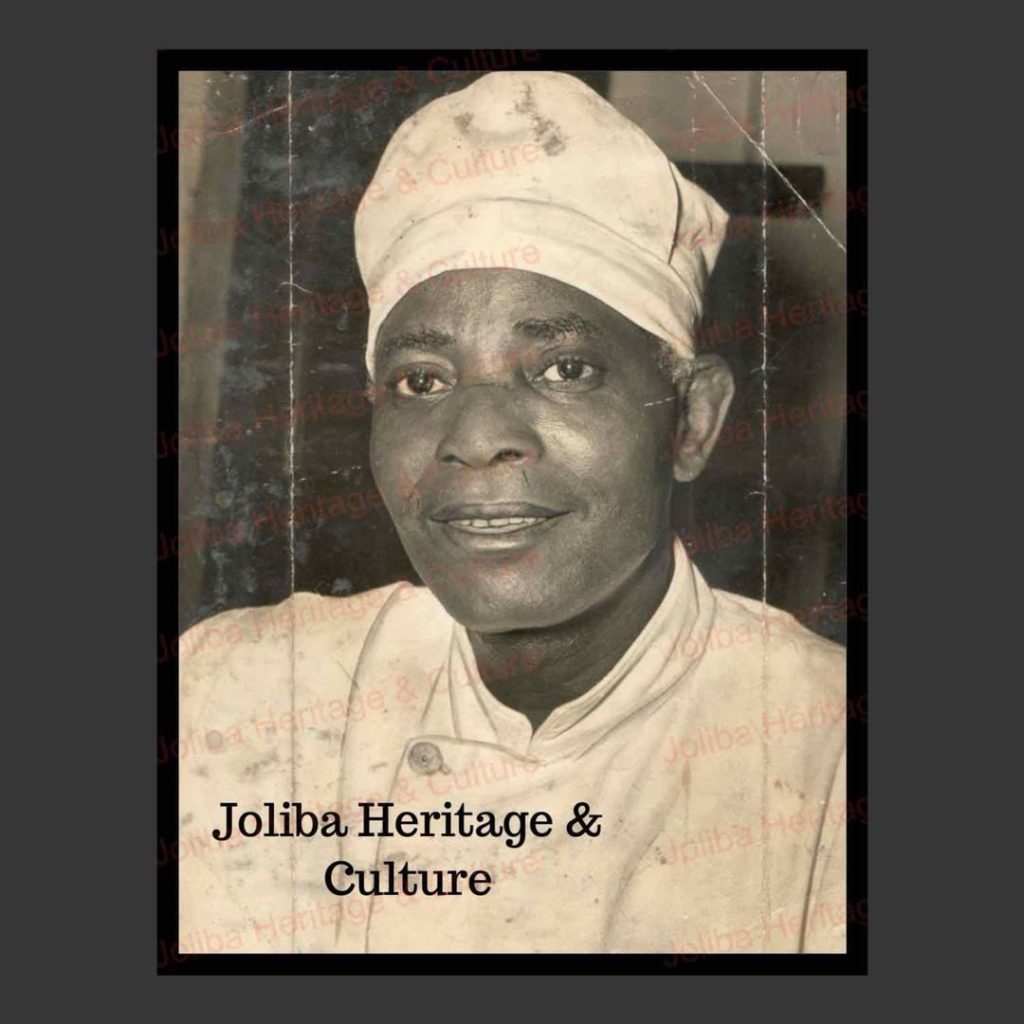

Carroll Harris Simms was an internationally-renowned sculptor and ceramicist who grew up in Toledo. Educated at the Toledo Museum of Art School of Design in 1945-46, thanks to a generous scholarship from Toledo philanthropist and art collector Mrs. McKelvy, he received his MFA at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1950.

Carroll Harris Simms died in 2010 in Texas.

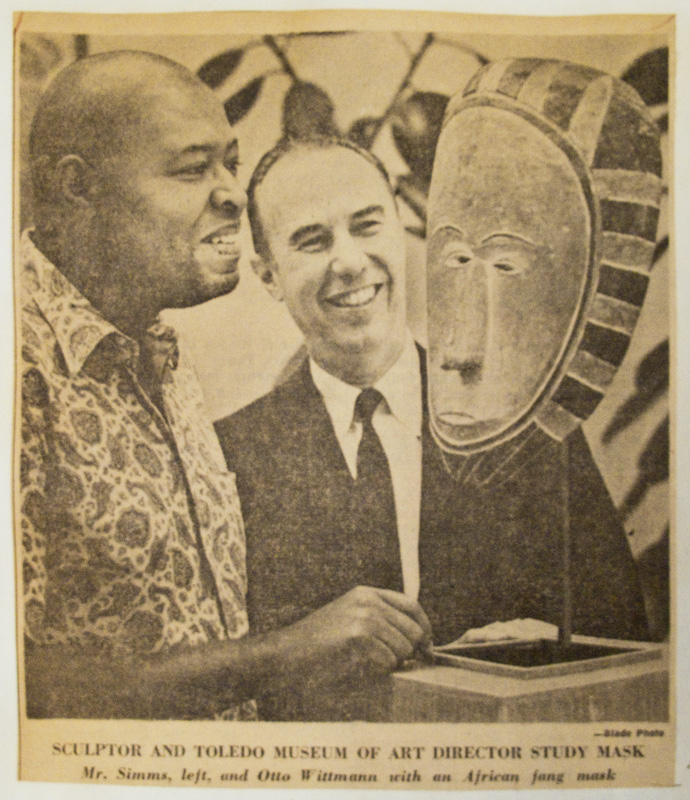

As a teacher, he wanted his students to draw from within themselves rather than emulate the masters. He lived in Nigeria for two years, not to study art but to soak up the culture. He was the recipient of two Fulbright scholarships to research West African art, in 1968 and 1971.

Sculptor Getting In Touch With His Art – Carroll Simms To Study Tribal Techniques In Nigeria The Blade, Aug 31, 1968: Sculptor Carroll Simms is American born, and he began his art training in Toledo. But through his fingers flow the feeling of darkest Africa, as he shapes strange figures – modern, yet with the flowing curves and elongated feature that hint of a tribal past.

In 1968 he was invited to create A Garden of Ancient Yoruba Pottery at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Among his international public works is a Negro crucifix

for St. Oswald Church in Tile Hill, Coventry, England.

He finds beauty in the “struggle of man’s existence because the gift of life is sacred and significant. Creative expression is worthy and symbolic of this truth.” For him art is “the universal spiritual force that makes the dignity, the heritage, and the origin of black culture inseparable from all existence.” A History of African-American Artists From 1792 to the Present

Carroll Simms showed his work in several Toledo Area Artists Exhibitions and won prizes in 1950 and 1951. In addition to the TAA shows, he was in a group show at the Toledo Museum with his Toledo contemporaries, a group called A.R.T. (Artists Round Table) in 1950. In 1951, the museum gave him a solo show. The museum classes and museum shows profoundly contributed to the artist he became.

The William Howze / Carroll Simms Documentary

interview of Carroll Simms with Jane Blaffer Owen

Interview recorded in July 2002. Kindly contributed to artistsoftoledo.com by the author, Bill Howze. The project was funded by the Susan Vaughan Foundation, Houston, and recorded by Bill Howze. See video clips at this link: https://carrollharrissimms.blogspot.com/

Some Highlights

Simms talks about his influences, education and early career:

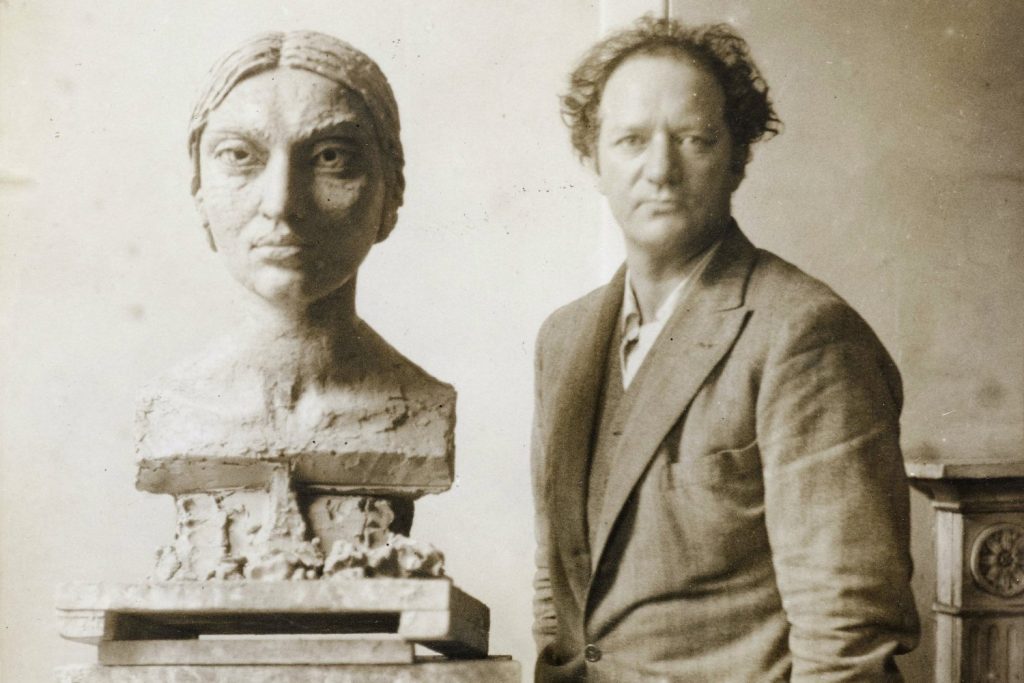

Simms grew up in Bald Knob, Arkansas, during segregation, where his mother brought home discarded magazines from white households. This is how he first encountered the work of Jacob Epstein, a major influence. “Life had maybe a six-page spread of Jacob Epstein sculpture… That’s where I was introduced to him.”

Cranbrook was a formative place for Simms. It was there he met fellow artist Patricia Paslov and encountered ideas from the avant-garde school Black Mountain. He was mentored by Mr. McVey, a sculptor who told him: “You know, I bet you could trace your people back to West Africa to the Benin people… because of your nose and your lips.” Simms recalled this years later when the Oba of Benin remarked on their resemblance.

Simms earned a Fulbright (1954-1956) to study sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art in London—thanks to the persistence of his pastor, Reverend Elliott Mason. “Reverend Mason said… ‘You have nothing to lose… just send it in!’ So I sent it in on time. And luckily, I won.”

His principal tutor at the Slade was Reginald Butler, a well-known British sculptor.

He made regular visits to the British Museum to photograph African sculptures. His deep curiosity was fostered by a relationship with William Fagg, a renowned British ethnologist. “I could go to any case and pick out the sculptures I wanted… they had a porter to follow me around… rope off the floor, so the tourists wouldn’t bother me.”

Trip to Africa

Simms’ access to Nigeria was blocked due to civil unrest, but Jane Blaffer Owen and the British Consul intervened to secure his visa. “I’m the president of the English Speaking Union… I can have an audience with the British Consular General… and show him your papers.” This led to direct support from Lagos via the State Department in Washington.

In Nigeria, Simms immersed himself in African sculpture and heritage. He lived with a Benin family and met the Oba of Benin, who was struck by Simms’ resemblance to him. “The Oba… looked at me… and then he said, <laughs>.

My mind went straight back to Mr. McVey. But it was true! And then when I got home (to my host family) and they asked me at the dinner table… and I told her what happened. She said, “Well, he ought to! You look just like him!” <laughs> And it was true, yeah.”

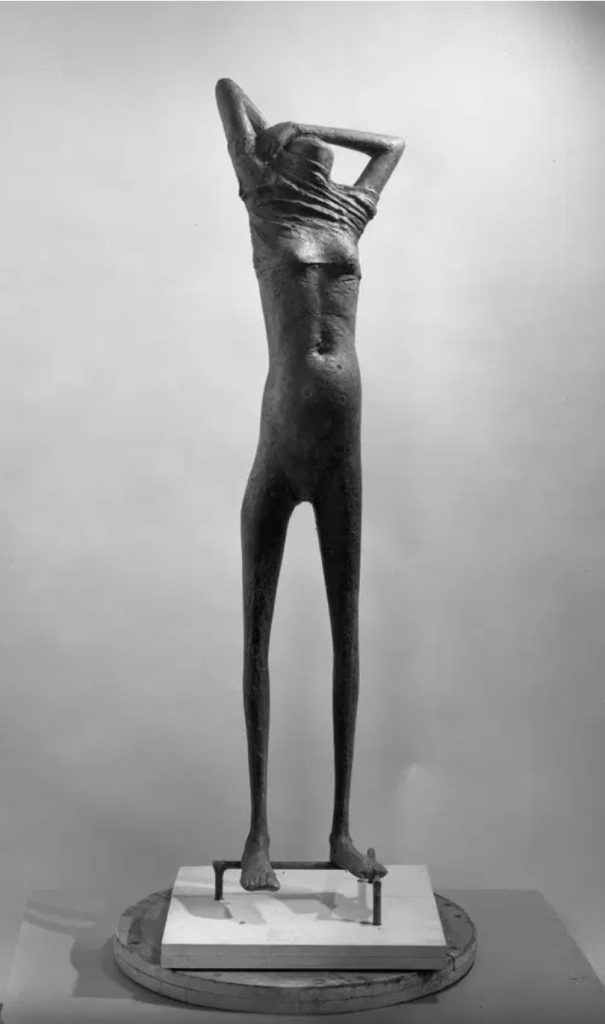

Simms rejected being labeled an abstract artist: “My work is not abstract! It’s symbolic. That means I can talk about it. And I can tell you where I started and where I’m going with it.”

Despite revering Epstein, he didn’t emulate his figurative style: “I am not a figurative person. I’ve turned down several commissions to do sculptures… even of Martin Luther King.”

Simms’ African travels influenced a major piece: a fertility-themed fountain at Texas Southern University. Inspired by Ghanaian cosmology, it features symbols for the moon (Mamay), stars (Pickens), and sun (Papay), along with alligators—guardians in a myth of protection. “This is why I have the alligator symbol in that fountain… Her face at the top, that’s like a three-quarter moon. That’s Mamay. It’s all fertility.”

African Queen Mother, Houston, Texas 1964